VIPs

- Mitch McConnell has agreed to go along with raising the debt ceiling by $480 million, keeping things open through early December; while this gives time for Democrats to raise it again through reconciliation, negotiations between party factions remain a roadblock

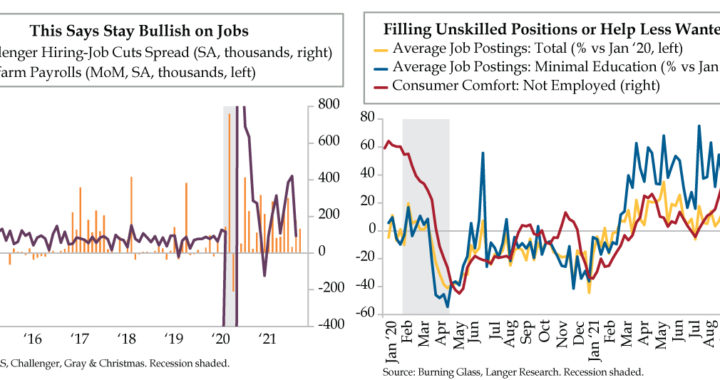

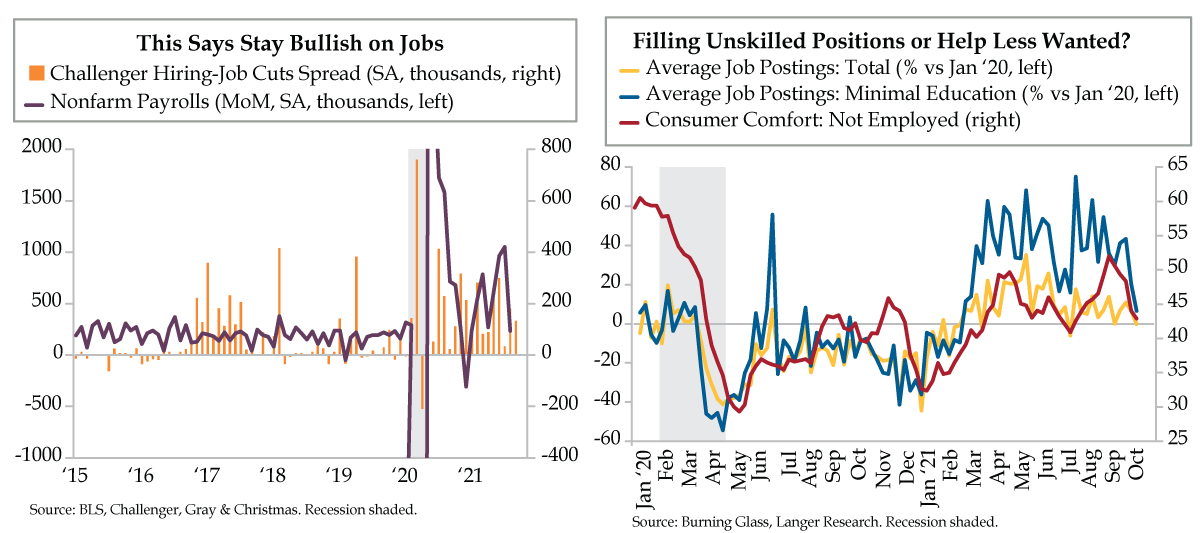

- Challenger’s Hiring-Layoff announcement spread remains robust, and the series’ correlation with nonfarm payrolls suggests a September gain near the consensus 500,000; however, strength could put added pressure on Powell at his November presser to announce tapering

- Per Burning Glass, nationwide job postings have slipped into negative territory vs. January 2020 levels for the first time in three months; meanwhile, job postings requiring “Minimal Education” are up just 6.5%, the lowest print since February and well off May’s 68.2% peak

“I wouldn’t do that if I were you. If I were you, I’d put him back. It can only lead to self-destruction. It only takes one bird to start you, and before you know it, it’s two birds, then three. Suddenly without realizing it, you’re a victim. Then one day…the end of the road.”

Clarence, Birds Anonymous, Looney Tunes, 1957

The moral: Always think twice before taking that first step into the abyss. While we look back and smile at Sylvester’s being talked back from the ledge, presumably saving Tweety Bird a horrific fate, Clarence’s guidance might have been inspired by a real-world event. On November 16, 1952, the Victoria Advocate ran a story accompanied by a photo of a kitty with a most chagrined look on its face. A random accident – a stray cat locked into a department store overnight – culminated with store officials happening upon the accused feline sitting at the side of what had been a toppled cage that had once housed five canaries, with its spring door sprung open. The only witness to the massacre was a lone canary in an elevated cage.

The phrase, “the cat that ate the canary” has since become a prized purview of political columnists. Though we’ve not yet read today’s recap, an astute Beltway veteran of the press should have ascribed this characterization to one Mitch McConnell in recapping the last few tumultuous weeks on the Hill. While the stock market breathed a huge sigh of relief, shrewd politicos didn’t dare declare victory for one side or the other. For weeks, the Democrats have decried the lack of time to raise the debt ceiling via reconciliation – which only requires 50 Senate votes straight up on party lines. No doubt, this more arduous path requires weeks, if not a month. Still, Senate Majority Leader Schumer was posturing, knowing he’d say and do anything to avoid having his party “own” a $7 trillion increase in the debt ceiling.

And so, with a canary feather barely visibly escaping his lips, McConnell graciously offered $480 billion to keep the U.S. government running through December 3rd and all the time the Democrats need to increase the debt limit between now and then…all by themselves. Will this time resolve the fissures that have opened within the Democratic party? Will a compromised, slimmed down social spending bill’s crafting be assured despite progressives losing their green initiatives and tax hikes to achieve resolution? We ask your indulgence and reply, “Hell no!” But it was time that was “requested,” and time delivered on the part of the GOP. Would McConnell repeat this ruse every two months all the way up to the Midterm elections? With further indulgence, “Hell yes!”

Into this political maelstrom steps one Jerome Powell who went to sleep last night praying for a weak jobs report. Say what you will about his Put being bigger than any of his predecessors. Be that as it may, the chair of the Federal Reserve respects the institution. To uphold its (false) image of being apolitical, the Fed holds tight to the tradition of not making any major policy changes when there’s brinksmanship on steroids in D.C. For good measure, December is a nonstarter as it’s unseemly to change policy with the holidays upon us.

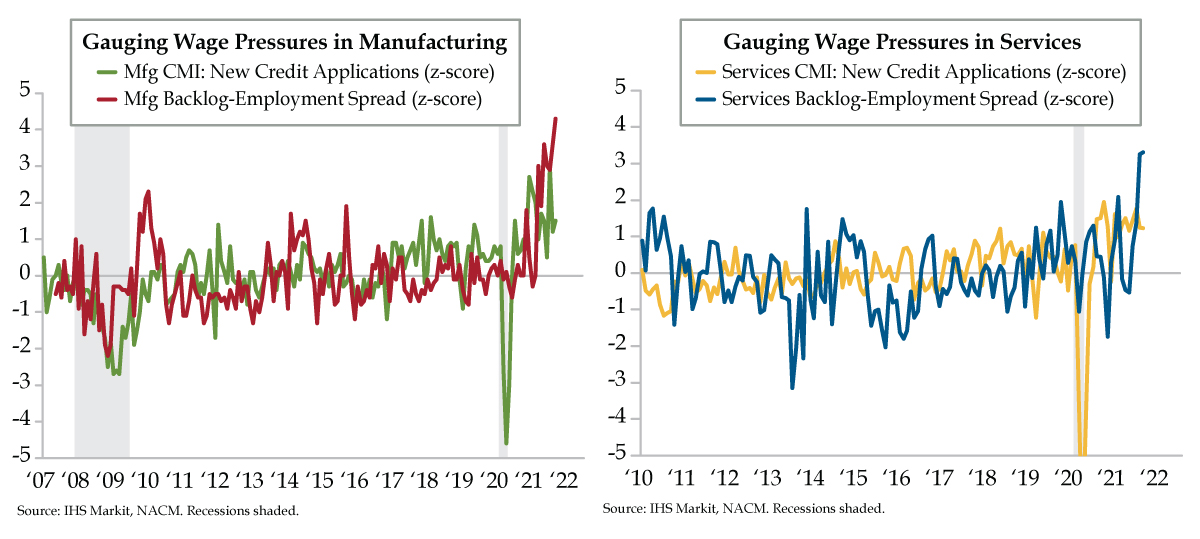

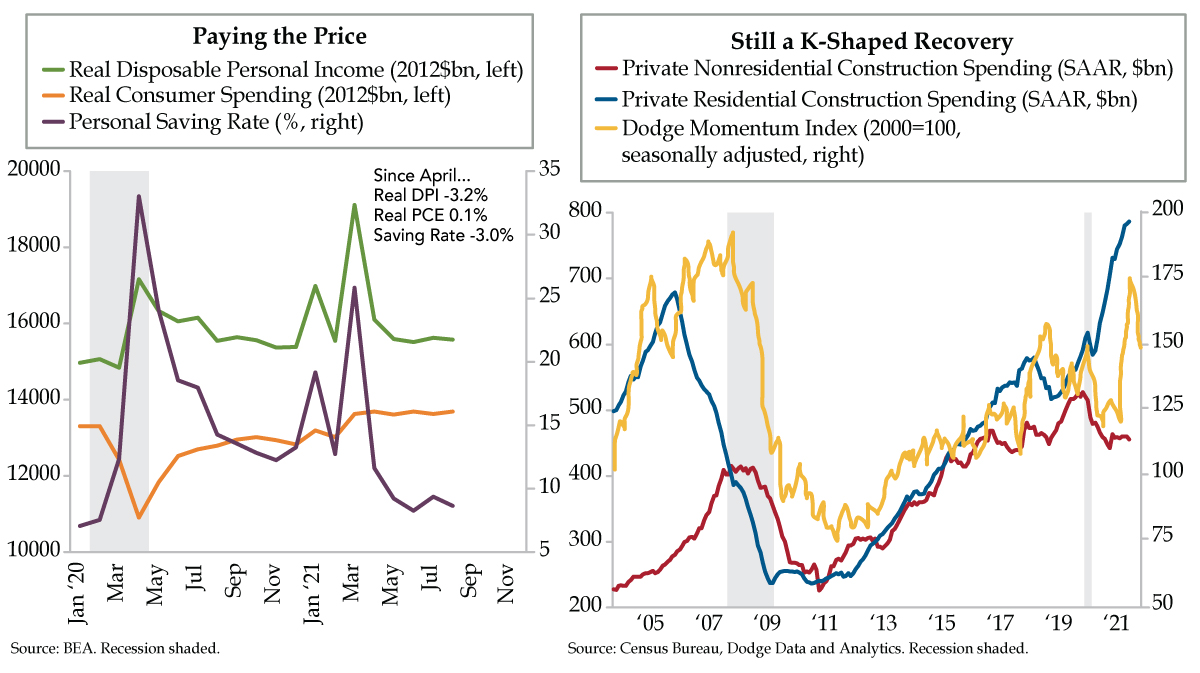

Today’s left chart, however, suggests Powell will be in something of a pickle come November 3rd, when he’s next prompted to the podium for a post-FOMC presser. The last time he was at that same virtual post, he pledged to pull the taper trigger at the November meeting if this morning’s nonfarm (NFP) payrolls did not disappointment. Given Challenger’s hiring announcements are still relatively robust vis-à-vis layoffs (orange line vs purple line), the two series’ historical co-movement suggests monthly payrolls should not leave the consensus, which has coalesced around a neat gain of 500,000, despondent. Bloomberg figures the headline print could come in at half that level and still satisfy the “substantial further progress” criteria.

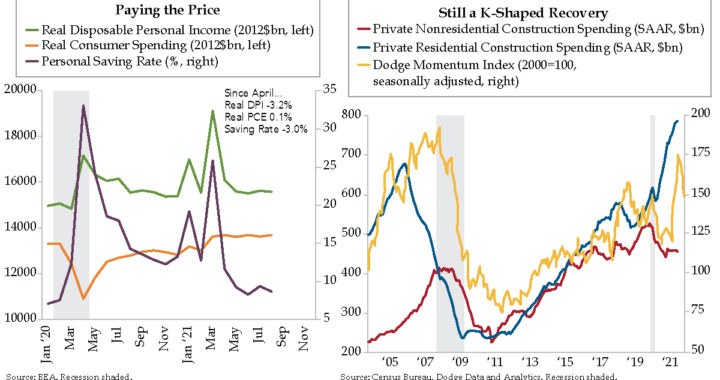

Zooming in closer to weekly data points for clues, what we should expect regardless of where that top line figure comes in is a welcome increase in the labor force participation rate. Let’s start with the not so chipper set. As you see in the red line, per Langer’s weekly consumer comfort data, the mood amongst those who are not gainfully employed has fallen to the lowest since mid-July. The flip side is in the job postings data. According to Burning Glass, against a benchmark of January 2020, nationwide job postings (yellow line) have slipped into contraction for the first time since this past July.

Before drawing any conclusions about a July pattern forming, the newest news we painted in today’s right graph was in the color of blue. While still up by 6.5%, the last time jobs requiring “Minimal Education” were so infirm was February. To think that in mid-May, these Help Wanted postings (the ones you see around your neighborhoods on handwritten signs) were up a post-pandemic peak of 68.2%.

Those hard-to-fill vacancies appear to be less vacant, and that’s a good thing. If you want validation, focus on this morning’s workweek – that’s where our sights will be set. In the meantime, we’ve got popcorn and a front row seat to what the naïve portray as Kabuki theater in the U.S. capitol. As we’ve long maintained, Minority Leader McConnell is in it to win it.