VIPs

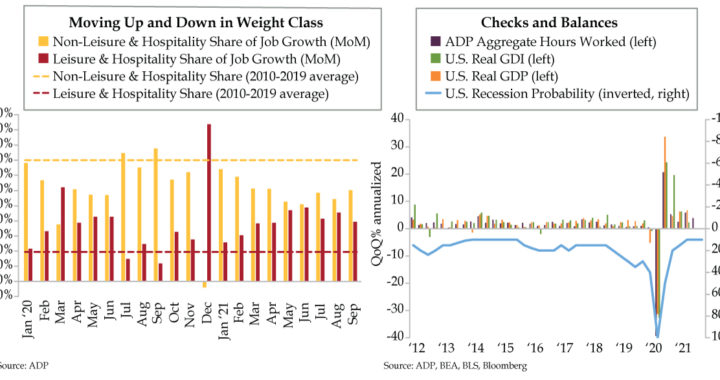

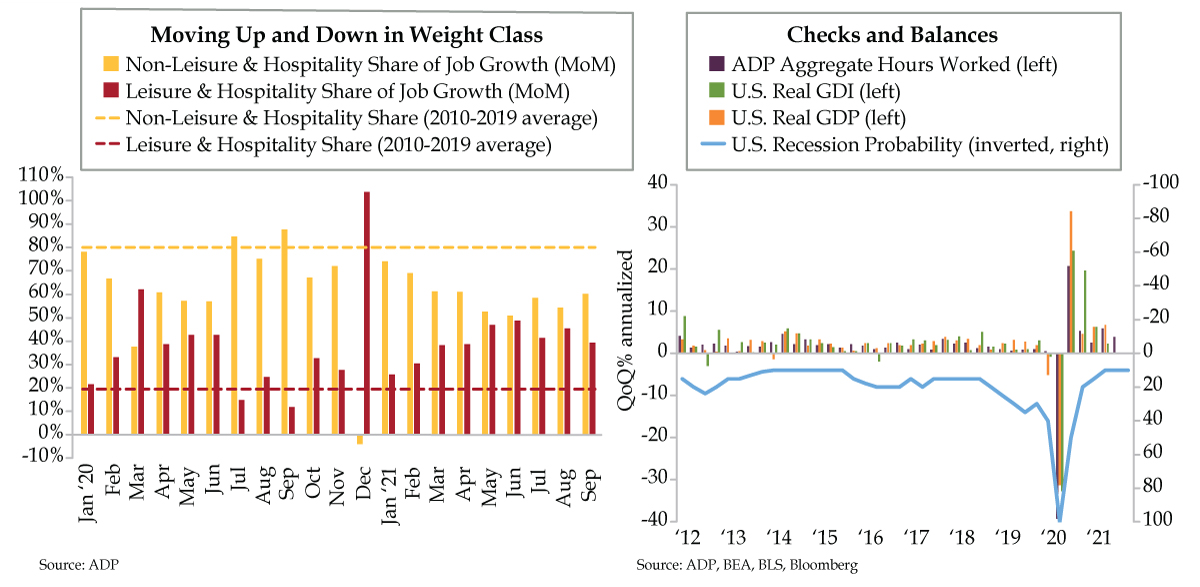

- Since April 2020, roughly 40% of job gains have come from leisure & hospitality, per ADP, well above the 20% average from 2010-2019; meanwhile, non-leisure has underperformed in the post-pandemic environment, seeing just 60% of job gains vs. 80% in the decade prior

- ADP’s September payroll report saw a gain of 568,000, well above August’s initially reported 330,000; sectors underperforming headline growth included professional services and trade/transportation while manufacturing, education, and healthcare outperformed

- Since 2006, ADP Aggregate Hours Worked have had correlations of 0.9 and 0.88 to real GDP growth and real GDI growth, respectively; assuming the workweek is unchanged at 34.7 hours from August, ADP suggests a 4% QoQ annualized rate of expansion in Q3

Halloween’s origins date back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in). The Celts, who thrived 2,000 years ago, celebrated their new year on November 1. This day marked the end of summer and harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold winter, which was often associated with human death. Celts believed that on the night before the new year, the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead became blurred. On the night of October 31, they celebrated Samhain, when it was believed that the ghosts of the dead returned to earth. Over time, Halloween evolved into a day of activities like trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, festive gatherings, and especially, donning costumes. According to the National Retail Federation’s Annual 2021 Halloween Spending Survey, 2021’s top three costumes entail more than 1.8 million children dressing as Spiderman, about 1.6 million as their favorite princess, and roughly 1.2 million as Batman.

The act of outfitting economics can require costumes be donned for long calendric periods. At times, entrenched trends can be dislodged for extended periods, measured in months or years. The COVID-19 pandemic shock qualifies as one such disruptor. Eighteen months after landing on U.S. shores, its ripple effects are still evident. Yesterday’s ADP employment report is a case in point.

The leisure & hospitality (L&H) sector was ground zero for the pandemic, which we would add has been a global phenomenon. We know we’re not breaking any new ground here. But for an industry that made up 13% of total private payrolls before the pandemic, a disproportionate 40% of the total job losses at the height of the health crisis in March and April of 2020 were in this area. From that point forward, an average of 40% of the job gains in the post-COVID recovery also came from this heavily consumer-facing part of the labor market (red bars). This was twice the average over the prior economic expansion from 2010 to 2019 (red dashed line). L&H didn’t just get into costume, it’s been punching above its weight class.

For completeness, the contribution to the recovery in private employment by industries outside of L&H stepped down in class over the last 18 months. Non-L&H job growth accounted for six in ten private payroll jobs on average (yellow bars), a notable step down from the eight in ten (yellow dashed line) that prevailed over the prior decade.

To put the labor cycle into perspective, we also use a simple calculation that projects the current month’s gain in ADP forward until the level of employment reaches full recovery. August’s initially reported 330,000 advance projected January 2023 as the month when the hole from COVID would completely be filled. September’s 568,000 gain shortened that timeframe to July 2022.

Let’s go granular. Taking this analysis down one level to the major sectors, L&H is the only one consistent with the headline number. Outperformers, or industries that would recover sooner, include construction, financial, natural resources, education, manufacturing and health care. Underperformers, or industries that would recover later, include “other” services, professional & business services, trade/transportation/utilities and information.

ADP’s claim to fame is as a guide for the granddaddy of all economic indicators — nonfarm payrolls (NFP). The ADP report allows for a recalculation by some forecasters two days before NFP hits the tape. As of this writing, the median of those restating their payroll calls was 550,000. This whisper number compares to the 488,000 consensus from all other economists who didn’t hit the rewrite button yesterday.

ADP also can be used as part of a checks and balances exercise for the near-term economic outlook. To clarify a point made in our prior missive, the slowdown narrative mentioned was not meant to generate a recession scare, the likes of which would bring out the Street’s Chicken Littles. It was done to call attention to the potential misalignment of consensus expectations and the surprise factor that could unfold when chasing forecasts down becomes more visible.

The coming downshift in U.S. growth can be confirmed – or denied – by observing the path of aggregate hours worked in monthly payrolls data. This labor input, which is the number of jobs times the average workweek for the private sector, is a well-regarded leading indicator. ADP’s early release can proxy the official data.

The sky is not falling. As illustrated in the purple bars and assuming the workweek is unchanged at 34.7 hours, ADP suggests a 4% quarter-over-quarter annualized rate of expansion in the third quarter. Since 2006, the ADP figure has a .90 correlation to real GDP growth (orange bars) and a .88 correlation to real GDI (gross domestic income, green bars) growth, the latter of which is a check against headline GDP.

We would add that at a purely intuitive level, something would be deeply amiss if we had not seen a pop in ADP job gains in the month supplemental jobless benefits programs expired. We already know consumption is falling among those who have not taken vacancies. We don’t think the U.S. economy is at the beginning of a dark, cold winter. However, the priced-to-perfection cycle low recession probability at 10% (inverted blue line) is likely at risk once the slowdown narrative is completely digested.