VIPs

- Bankruptcy filings for companies with at least $50 million in debt hit three in the week ended November 12 vs. nearly 15 seen in June 2020; though the Fed’s credit backstop limited creative destruction, corroded supply chains are pressuring firms that survived the pandemic

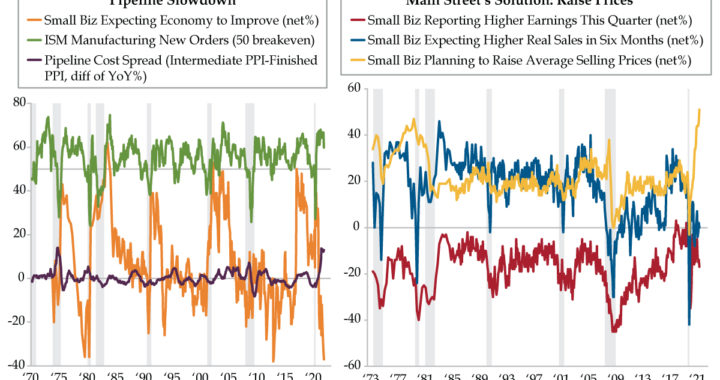

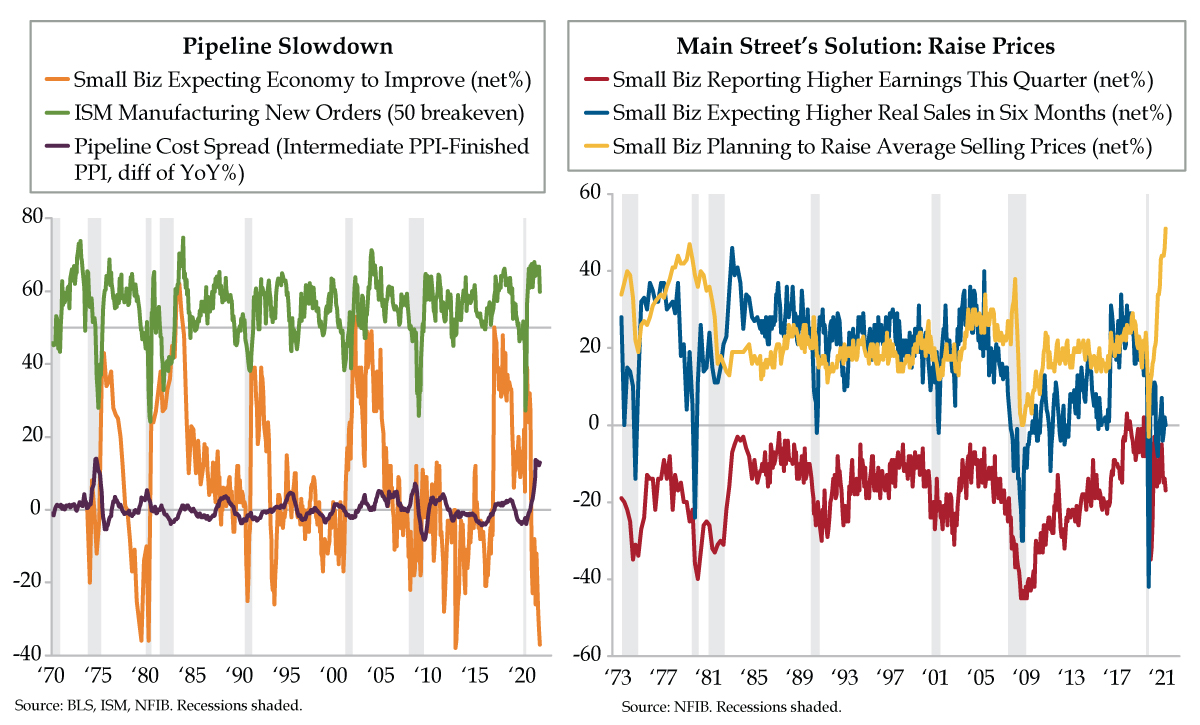

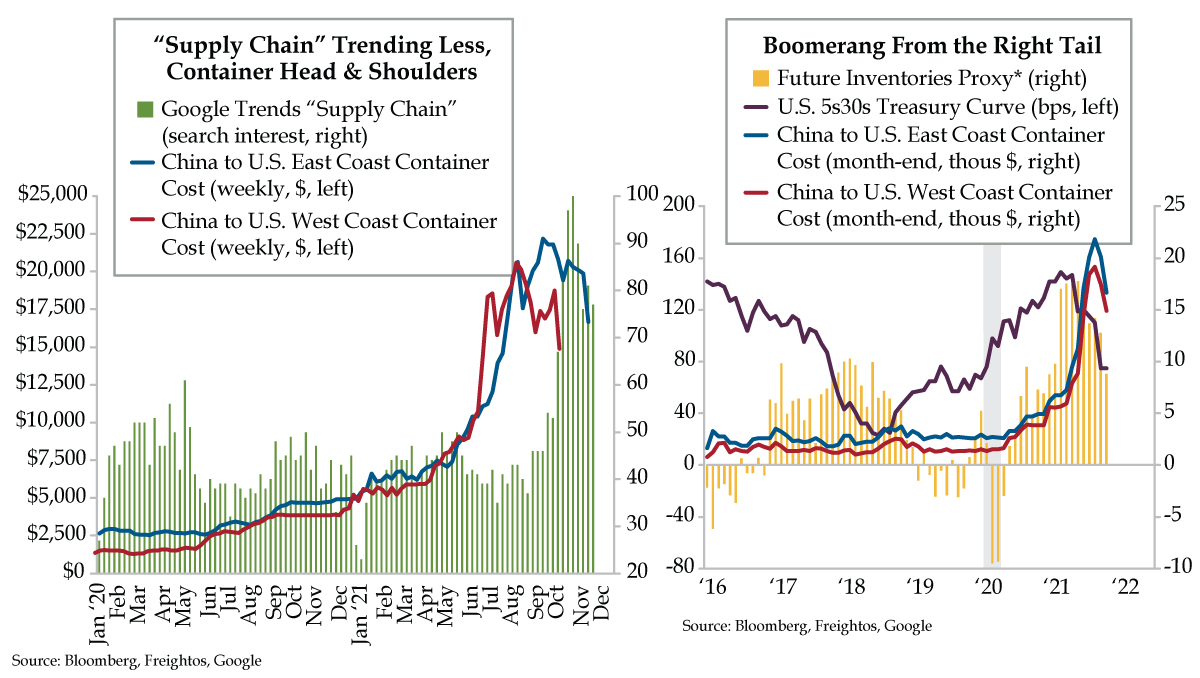

- An average of Future Inventories from regional Fed surveys suggests that panic buying by firms has subsided; the same message, which harms future GDP math, can be seen in the tightening of the 5s/30s curve corroborated by a decline in Google “Supply Chain” searches

- Per Freightos, container costs from China to the US’s East and West Coasts have finally begun to turn; should the downward trend continue, prices may begin to fall back down to Earth for consumers as well as for businesses struggling to manage elevated input costs

We all managed (our sanity) throughout the 2020 lockdown differently. My mom, who turns 75 this Sunday (Happy Early Birthday, Nana!), was a Type 2 Diabetic when the pandemic hit Cross, a Texas town so small you can’t find it on a map. There, she gardens outside her home on a small ranch I gifted her in my early 30s when I was on Wall Street (an oil company later fracked underneath the property, so it’s a gift that returns monthly royalties). While she took comorbidity seriously enough to shed diabetes, one pound at a time, she isolated in Iola until her second vaccination. With all that time on her hands, and unable to “go to town” in College Station to her hairdresser, she performed a labor of love – she grew her hair. When she emerged from her cocoon in the countryside, she donated 13 inches to Locks of Love (LOL), a nonprofit dedicated to helping children and young adults up to the age of 21 who have lost their hair as the result of cancer, severe burns or alopecia, a condition which manifests in hair loss and is age agnostic. Per LOL, due to the media’s embrace, its locks have reached thousands across “all 50 states and Canada.”

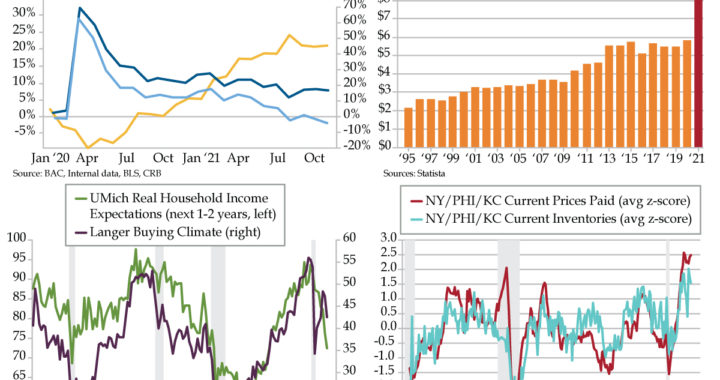

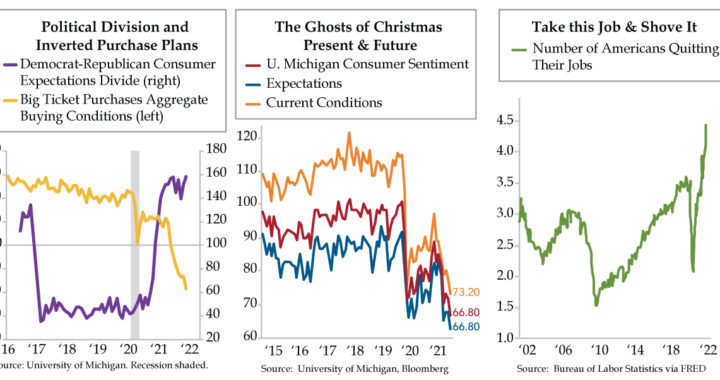

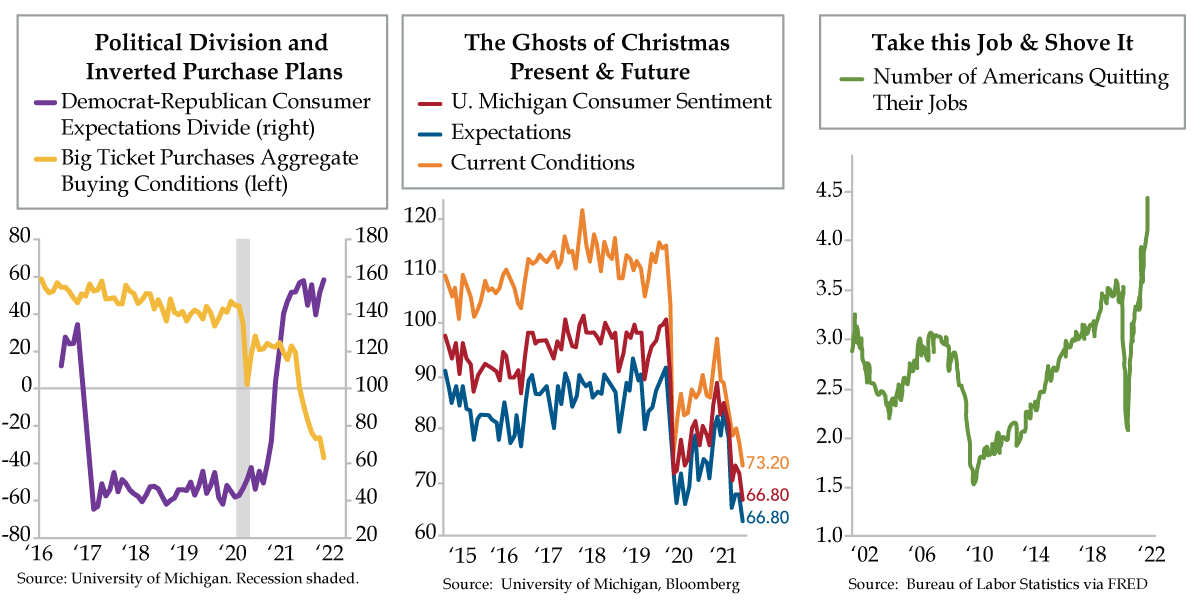

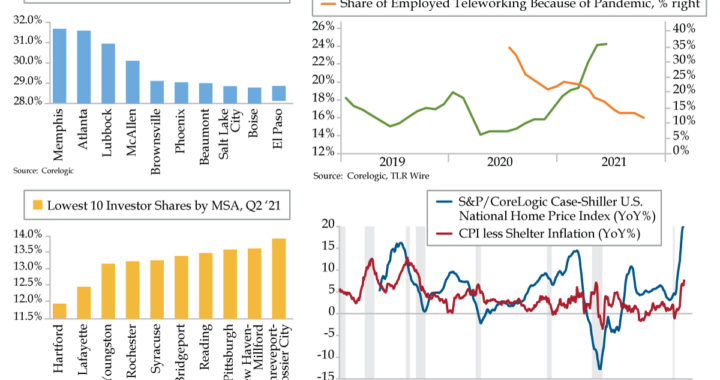

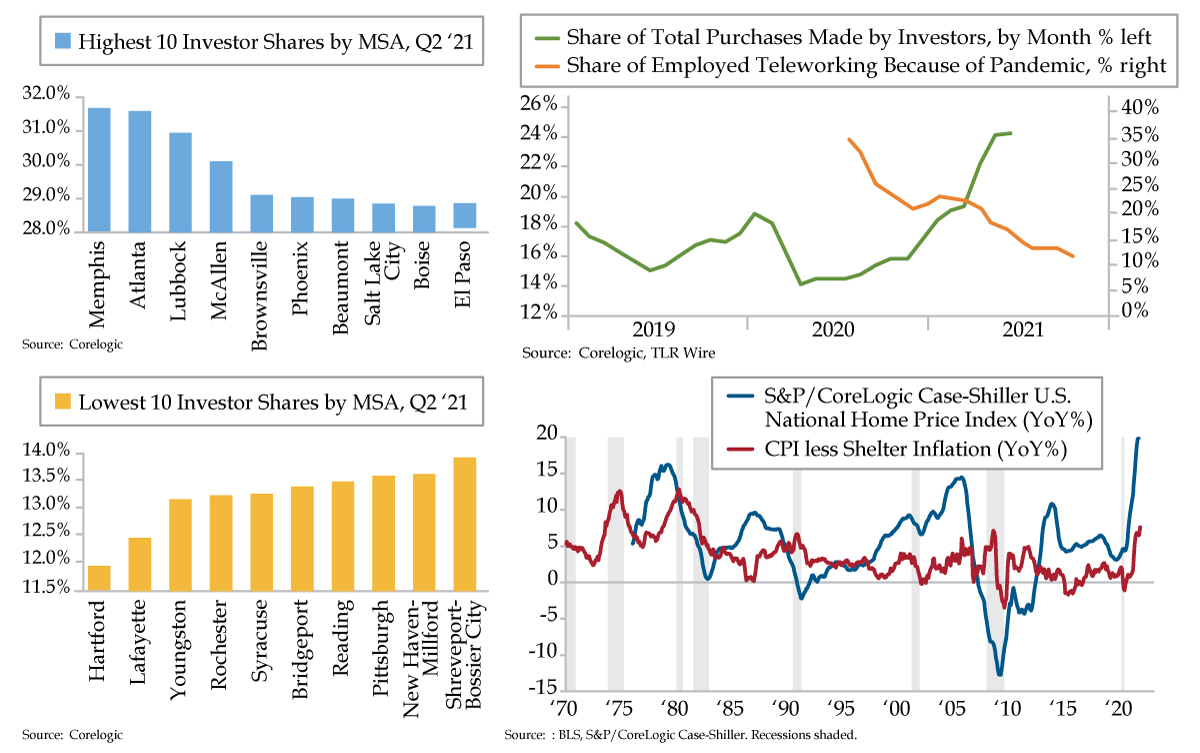

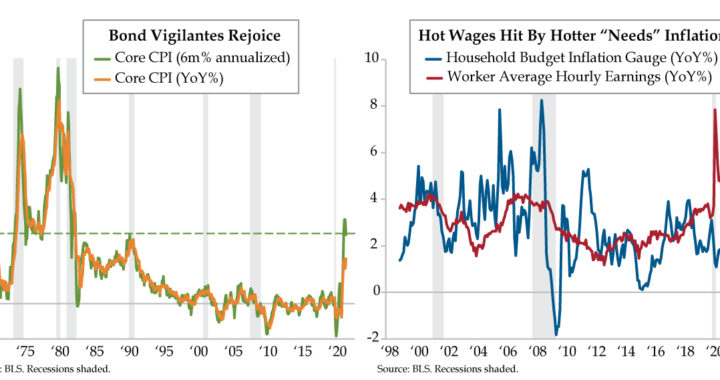

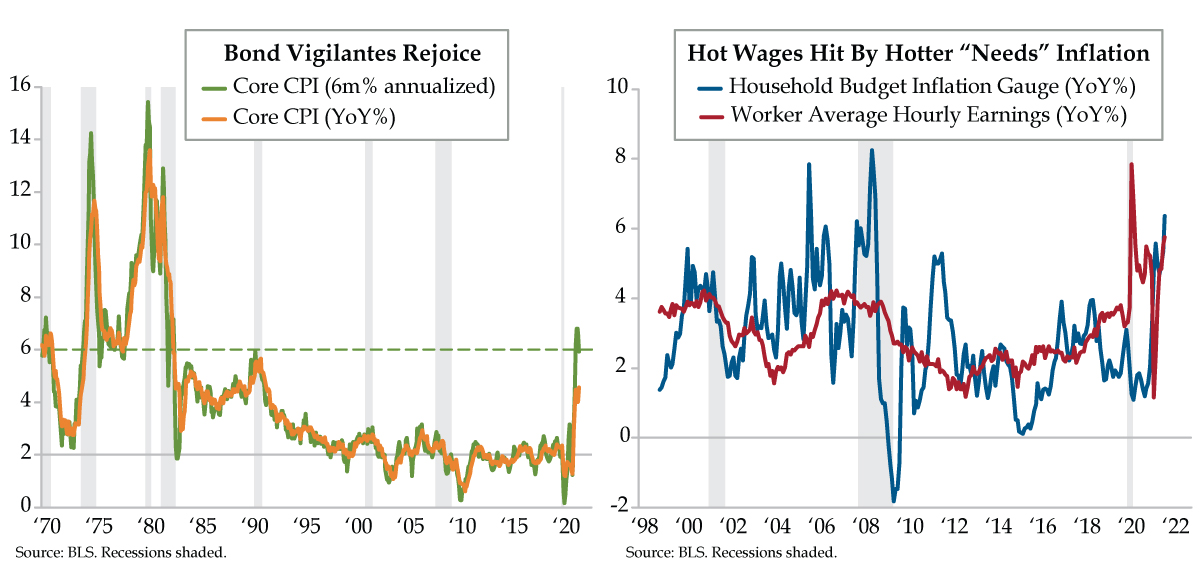

As a former central banker, I approach this Thanksgiving with utter humility and a sad sense of helplessness about the inflation my former employer has amplified by turbo-charging cruel fiscal largesse. You know I’ve been on a bacon shunning bandwagon, disgusted as I am by its in-your-face gaudy prices. Upon the occasion of visiting a Tom Thumb, a big Dallas grocery in the Safeway brand – I ended up in front of the bacon, chatting with the loveliest woman. We were both just staring at the prices. The best that can be said is that competitor, Kroger’s charges 50-cents more for a pound of Oscar Meyer; it was “only” $9.49 a pound at Tom Thumb. Her eyes full of sparkle, she said, “You know, I was talking to a friend of mine a few days ago. We said to each other, ‘Pretty soon, the only thing you’ll be able to walk out of Tom Thumb with, if you walk in with $10, is a half-gallon of milk.’” We chuckled at the truth of the matter, and I wished her a Happy Thanksgiving, and she me, as we pushed our carts past one another to move to the next source of sticker shock. But the brief exchange left me embarrassed to have dedicated nine years of my career to working for the same Fed that’s hurting such a large percentage of the American public. Powell et al have backed themselves into such a tight corner that they’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t tighten. Lower for longer had never failed them…until now.

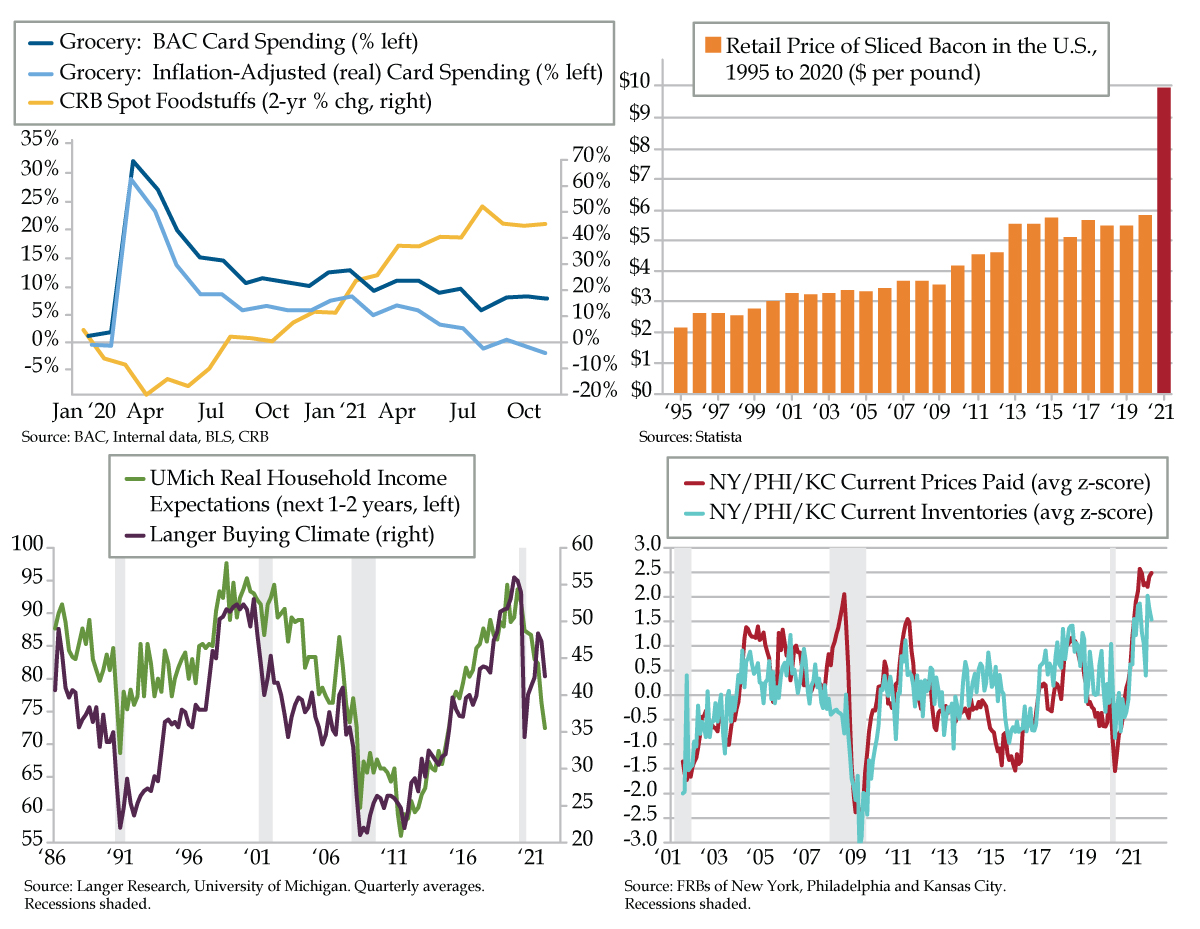

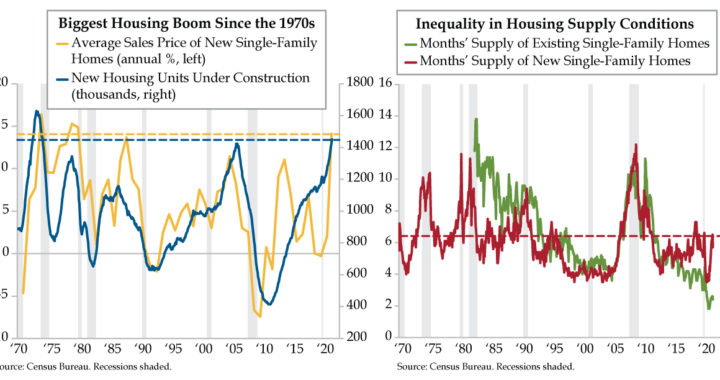

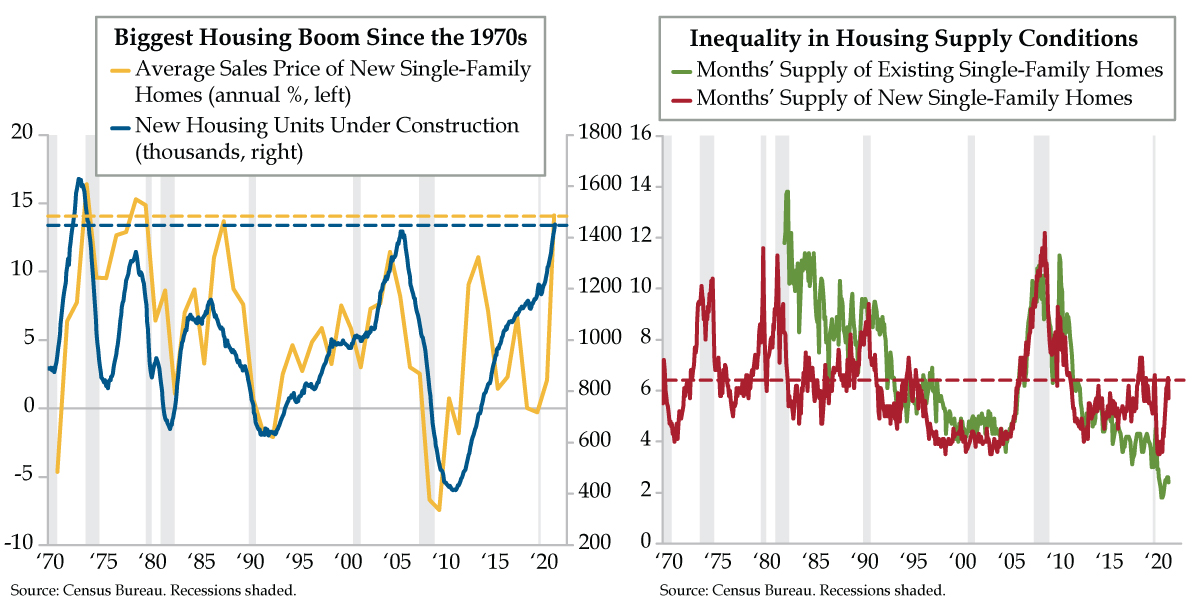

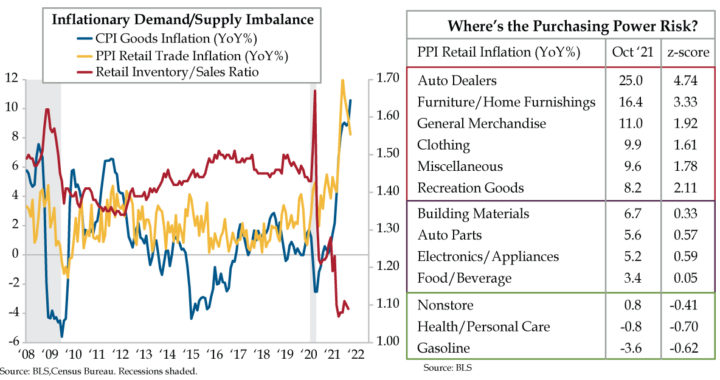

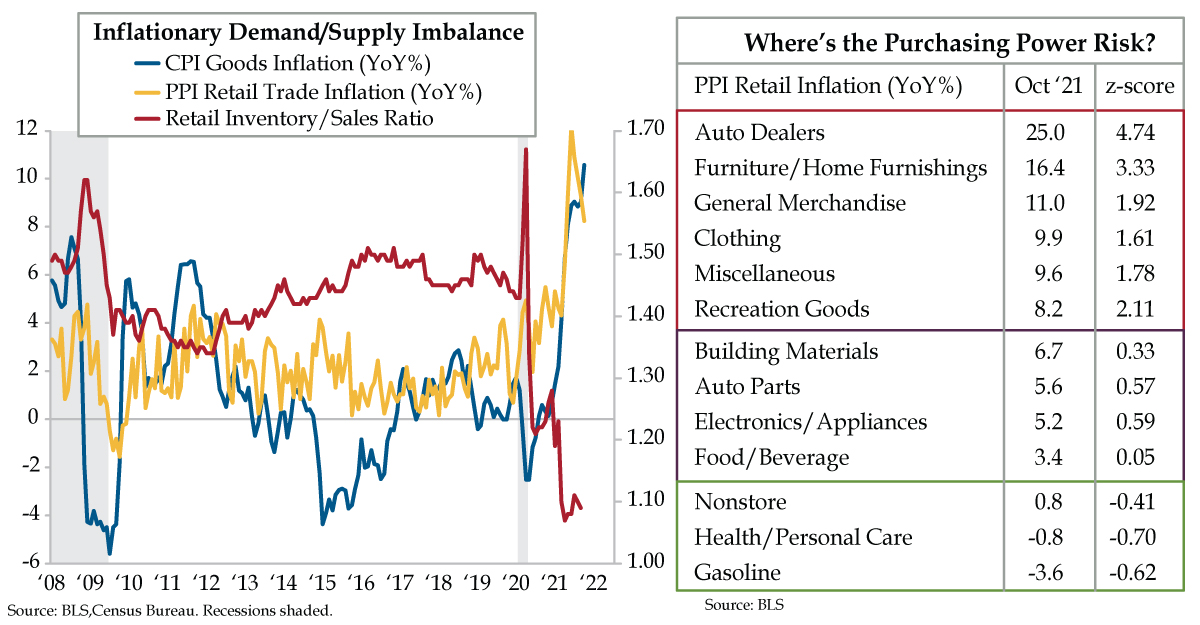

Today’s duo of charts hints at relief on the inflation front. In the “there’s no such thing as a free lunch” department, the graphs also suggest the demand side is cooling as pressure on the supply side begins to abate. The inspiration for the depictions du jour was a lonely Bloomberg headline from last Friday: “Default Threatens Companies Reeling from Frayed Supply Chains.” Default? Didn’t the Fed outlaw creative destruction on March 23, 2020?

For those of you unfamiliar with the term, in 1942, Joseph Schumpeter introduced the world to the idea of a “gale of creative destruction” unleashed by capitalistic forces which threatened the world Karl Marx idealized. The “process of industrial mutation that continuously revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating the new one” ensures fresh, fertile ground is laid such that there are more jobs created by new entrants vis-à-vis the now bankrupt entities.

In his quest to kill capitalism, with grit equal to George C. Patton, one Jerome Powell spearheaded Operation Kill Creative Destruction in March 2020. It worked. At its apex in June 2020, weekly bankruptcy filings by companies with at least $50 million in debt neared 15. In the week ended November 12, 2021, weekly filings had fallen to three, following a muted trend that’s emerged since last September. Creative Destruction appears to have been destroyed via fiscal and monetary stimulus joining forces.

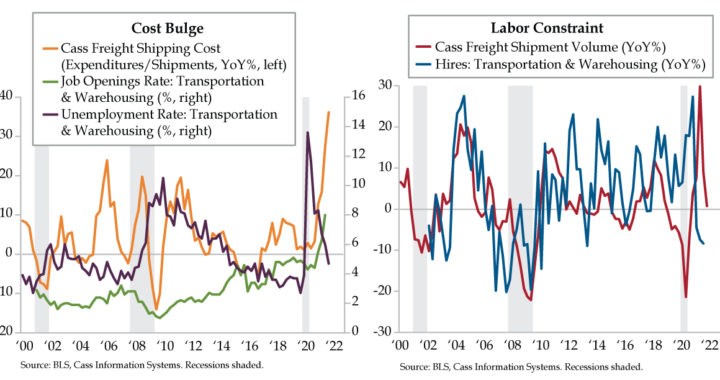

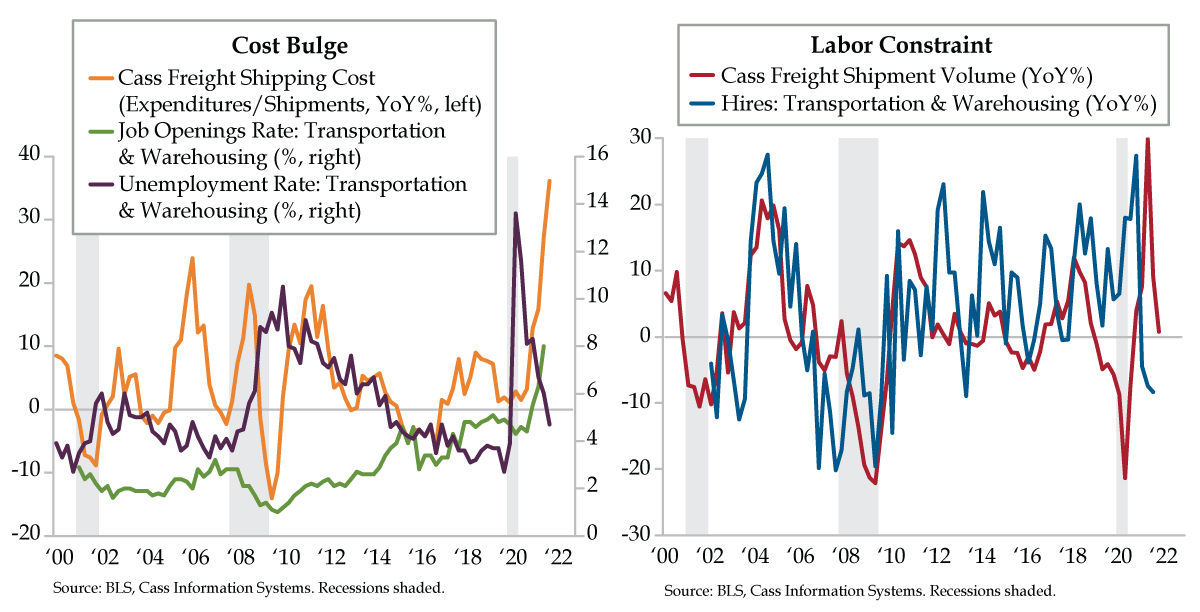

Per Bloomberg, however, “A growing cohort of smaller companies that survived the cold depths of the pandemic say now they’re in danger because the economy is too hot. Mattress sellers, flooring manufacturers and makers of clean energy equipment are warning that stretched supply chains

and runaway freight bills have pushed them to the brink of ruin.”

The funny thing that happens when inflation becomes so debilitating it starts to put companies into bankruptcy is that it starts to fix itself. Companies are also telling us they’ve begun to replenish their depleted stocks. An aggregate of Future Inventories gauged from the regional Fed manufacturing surveys (yellow bars) tells us the panic buying has subsided. That same message, which negatively harms future GDP math, is being broadcast by the spread between the yields of the 5- and 30-year Treasuries (purple line). Validating this soft data is the lessening in Google Trend searches for “Supply Chain” (green bars).

Though the March 1st Texas primaries are technically three months away, incumbents are already on the stump. Carping about debilitating inflation will thus prevent the good news in the red and blue lines from being well broadcast – that freight costs have finally begun to turn. We can only pray that lower prices swiftly follow for the most vulnerable the Fed has left behind.

Please join Quill Intelligence this holiday season by giving to your local food bank, church or charitable organization that directly helps the needy in the next month.