VIPs

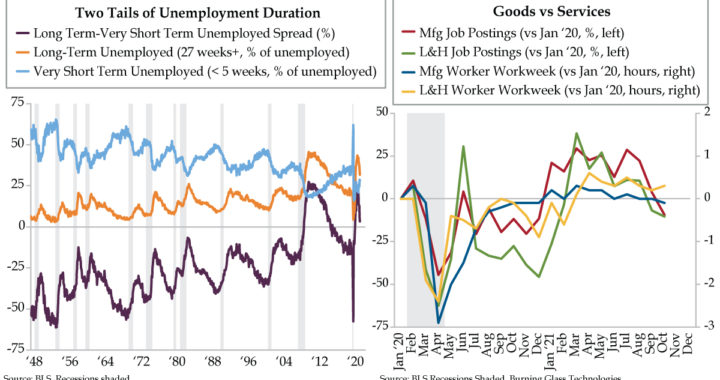

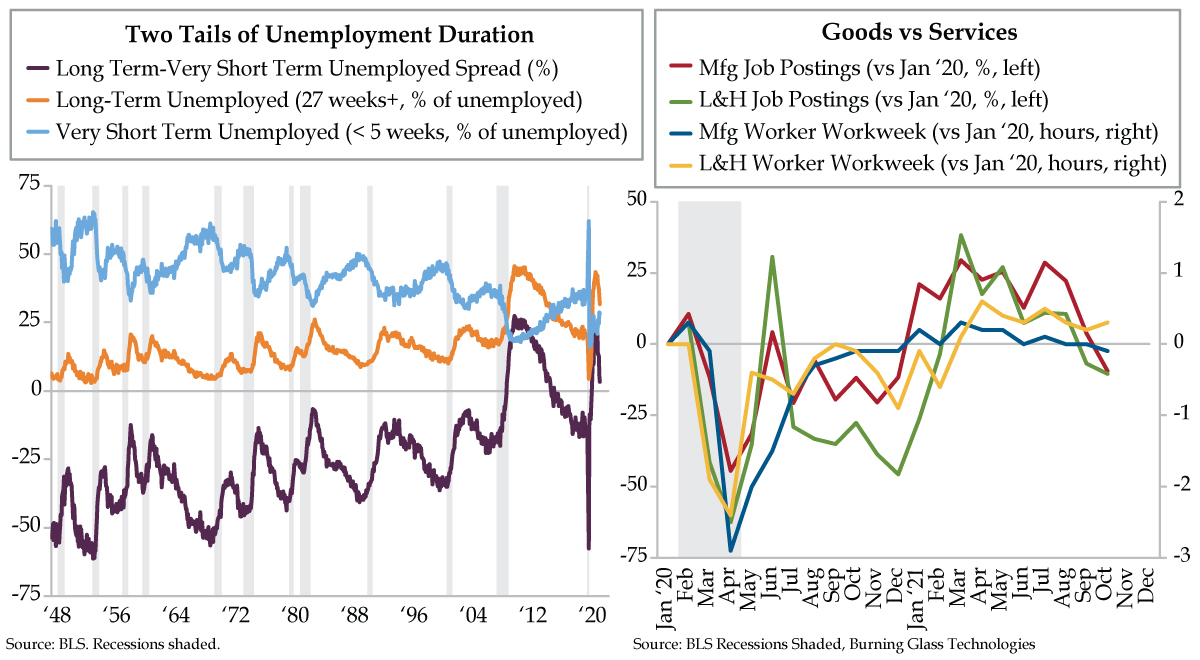

- At 28.3%, those who have been unemployed for fewer than five weeks are now at a post-pandemic high; meanwhile, 31.6% of the unemployed have been out of work for more than 27 weeks, a 13-month low but still well above the 19.3% registered in February 2020

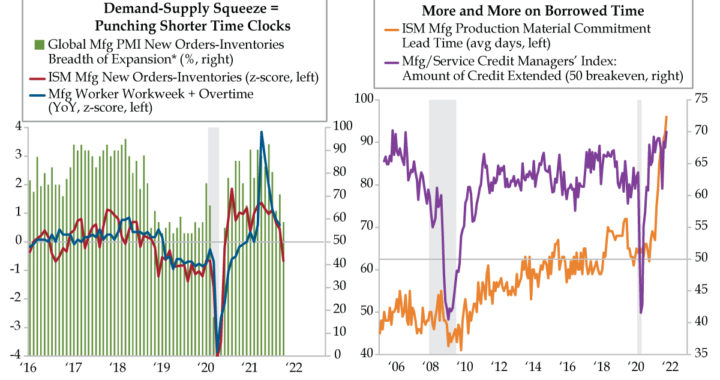

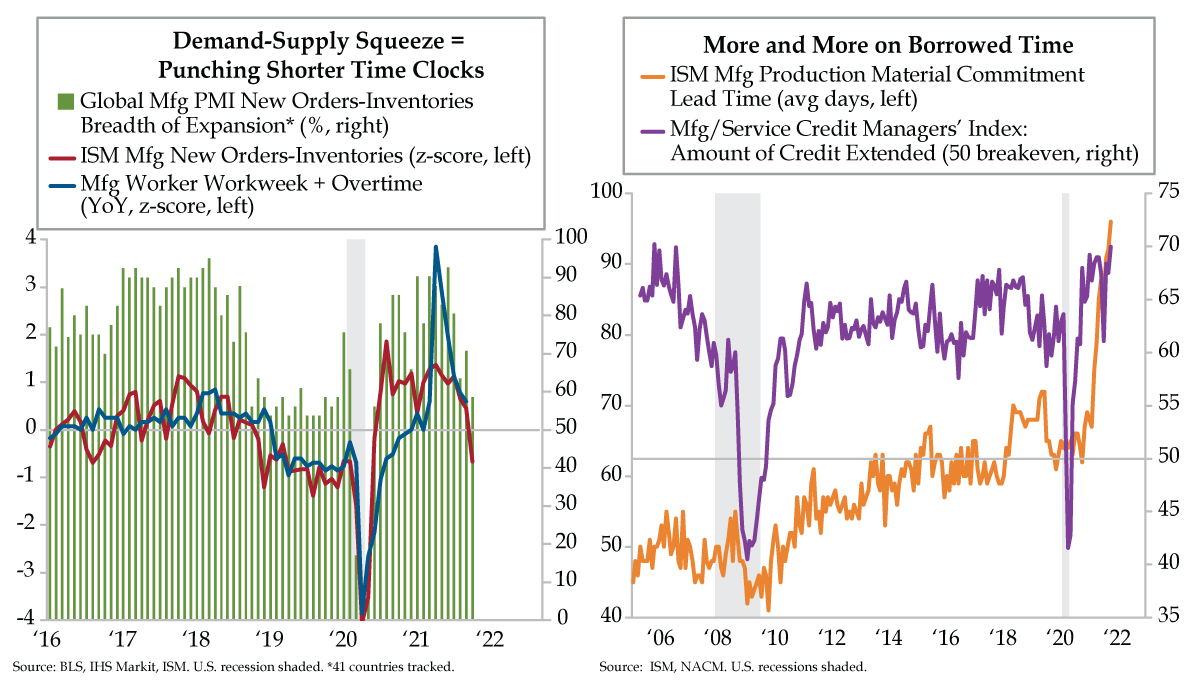

- After hitting a high of 41.7, the manufacturing worker workweek has fallen to 41.3, the lowest since December 2020; in leisure and hospitality, the workweek peaked at 25.3 hours in April with the last round of stimulus checks, before falling slipping back to 25.0

- Per Burning Glass, job openings in manufacturing are at -9.5% in the week ended October 29 vs. January 2020, the first negative read since last November; at -10.5%, leisure & hospitality openings have contracted for the last two weeks to their worst showing since January

“Mommy’s alright, Daddy’s alright

They just seem a little weird

Surrender, surrender

But don’t give yourself away”

Gotta love a true contrarian. Pushing back against the conventional wisdom and profiting is as good as it gets. Who knew this applied to musicians? In 1976, Cheap Trick first played “Surrender” on tour. The ‘70s anthem was subsequently recorded in studio and released in 1978. Isn’t the band supposed to first record and release the potential hit and then have its popularity carry over into lucrative concert tours? As if there isn’t enough irony in what you’ve just read, the first song featured on their third studio album, “Heaven Tonight,” tells a contrarian story of a teen’s realization that his parents weren’t uncool after all, despite the generational divide. Though the “teen” singing the song says his parents were “a little weird,” he then stumbled into their “rolling on the couch” listening to KISS records. To get into the right frame of mind to pen the lyrics, songwriter and lead guitarist Rick Nielson said he had to, “go back and put myself in the head of a 14-year-old.”

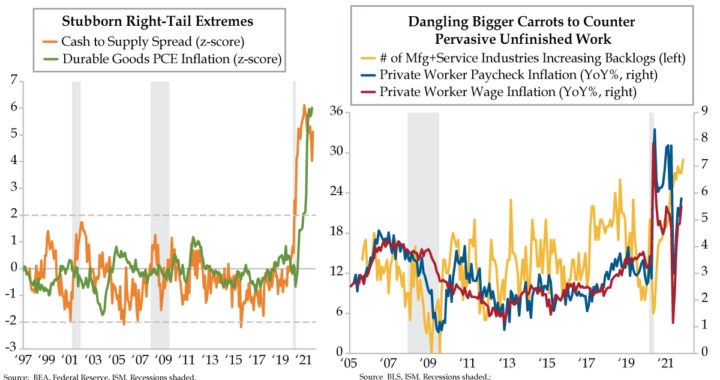

Economists and investors alike had to surrender to the reality of what appears to be full employment with wage inflation nowhere near retreat and signs that it’s pinching margins in the current quarter through which we’re nearly halfway through. On Friday, Factset’s John Butters noted that, “For Q4 2021, 41 S&P 500 companies have issued negative EPS guidance and 26 S&P 500 companies have issued positive EPS guidance.” While in line with the 5-year average, it’s still the mirror image of where we were three months ago when 29 firms were guiding negatively and 42 were telling investors to expect upside.

The bravado gainfully employed workers are brandishing was evident in those who’ve been unemployed for five weeks or less (light blue line). At 28.3%, these effective job hoppers as a percentage of the unemployed are at a post-pandemic high. If you’ll indulge some anecdata, here in Dallas, a colleague who runs the third-party logistics arm for a Fortune 100 had a new hire quit after two days in protest of being made to wear the same orange safety vest required of all warehouse workers.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the long-term (LT) unemployed. You know that we’ve been increasingly concerned about the element of scarring that’s becoming increasingly apparent, as in structural damage to the labor force. While the 31.6% of the pool of unemployed who’ve been out of the workforce for 27 weeks or more (orange line) is at a 13-month low, it’s still the highest since January 2015. The journey from that month’s 31.3% ended in February 2020, when it hit 19.3% before COVID-19 started wreaking havoc on the data. That datapoint marked “full employment” as defined by Federal Reserve officials.

Given the abrupt nature of the economic slowdown and the dim prospects for fresh rounds of nationwide stimulus checks, the risk is we may be approaching the current cycle’s lows in the percentage of LT unemployed.

What’s exceedingly rare is the percentage of LT unemployed being higher than that of the very short-term (VST) unemployed (purple line), a manifestation only seen in the past two cycles. The word “structural” once again rises to the fore.

The most cyclical parts of unemployment occupy the tails – LT and VST. These series gauge the bad vs. the good in the unemployment distribution. In the postwar period, VST trended above LT, which is intuitive in “the land of opportunity.” VST are seizing opportunities because they can easily secure a bigger paycheck. The last two cycles’ persistently high LT unemployment speaks to the permanent dislocation that’s made it more difficult for workers to become re-employed.

And here’s the linchpin via QI’s Dr. Gates: “This spread line shows that this IS NOT a theme unearthed because of COVID. It also happened after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). Throw in that productivity was downshifting before the GFC and seemed structurally lower over that entire episode. As a result, certain sectors may not have been able to carry the same labor share and jettisoned workers leaving a permanent scar on LT unemployed.”

One final note – this phenomenon is a novelty of the post-Quantitative Easing era. Can we be surprised that incentivizing the monopolization of the economy via the conduit of passive investing institutionalized by the Fed Put has permanently shrunken the labor force participation rate?

Today’s right chart certainly seems to concur with that conclusion. After reaching a high of 41.7, the manufacturing worker workweek (blue line) has slumped to 41.3, the lowest since last December. As for the media-hyped over-stretched Leisure & Hospitality (L&H) sector (yellow line), the workweek peaked at 25.3 in April 2021, the month those stimulus checks hit (which is surely a coincidence) and has since drifted to 25.0.

Employers not having to stretch their workers so thin should show up in reduced demand for fresh hires. Per Burning Glass Technologies real-time weekly data, at -9.5% in the week ended October 29 and vis-à-vis a January 2020 baseline, job openings for manufacturing positions (red line) are negative for the first time since last November. As for L&H openings at -10.5% (green line), they’ve been contracting for the last two weeks and are at their worst showing since this past January. To what are employers surrendering if not reduced demand?