VIPs

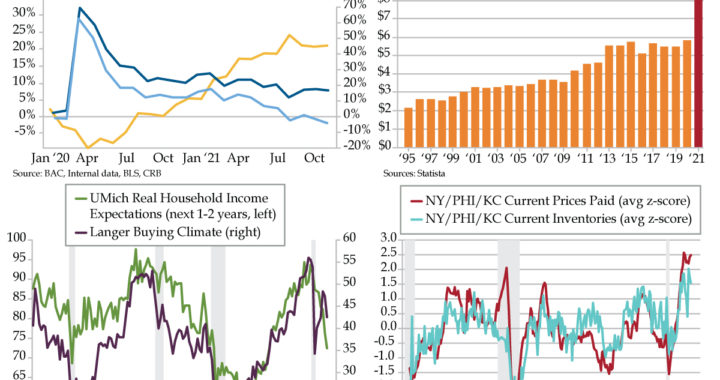

- Unit Labor Costs saw a spike to 8.3% in the third quarter, beating out the 7.4% consensus and soaring above Q2’s 1.1% rate; while labor costs grew at their fastest pace since 2014’s first quarter, productivity moved in the other direction with a 5% drop, its worst since 1981

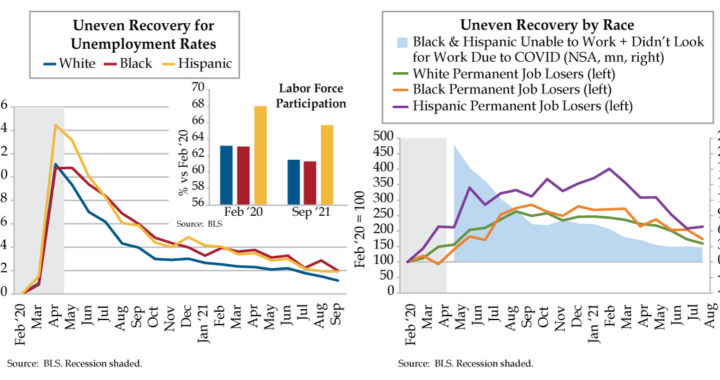

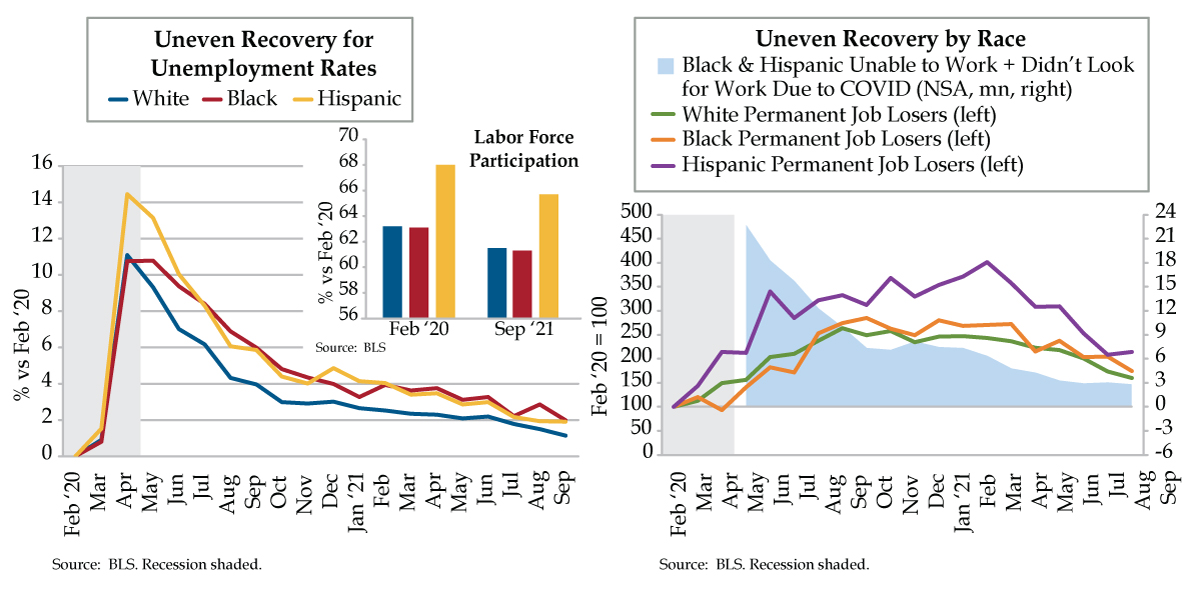

- The white LFPR has recovered to 65.7% from February 2020’s 68% vs. the black LFPR falling from 63.1% to 61.3% and the Hispanic LFPR from 63.2% to 61.5%; 2.8 million Black and Hispanic workers still remain out of work due to COVID and rising childcare costs

- The White unemployment rate is 1.1% above its February 2020 levels vs. 2.0% and 1.9% higher for Blacks and Hispanics, respectively; with minority groups seeing higher permanent job losses as well, recovery is far from the inclusiveness Powell aspires to achieve

You’d have thought that along with baseball and apple pie, fireworks would have been invented in the United States. But, baseball is the one and only real deal, having been started in 1845 when the rules were written by the New York Knickerbocker Club. As for the case of that iconic dessert, the first apple pie recipe was published in England in the 14th century. Fireworks date back even further and conjure images of naughty teenage boys tossing things into fires to see how they will react, which is sometimes with a bang. In the second century B.C. in ancient Liuyang, China, it was bamboo stalks that were being thrown into fires. The explosion that followed resulted from overheating the hollow air pockets unique to bamboo, which is a grass, not a tree. The Chinese believed that nature’s “firecrackers” warded off evil spirits. Roughly 2,700 years later, a Chinese alchemist mixed potassium, nitrate, sulfur and charcoal which became a black, flaky powder and was the world’s first gunpowder. Combine the old with the new by pouring this innovative powder into bamboo and voilà — the first man made fireworks.

Over the past week, fireworks have been going off aplenty on Wall Street. It started last Friday with the release of the third quarter Employment Cost Index. The economics community saw a rise coming – they’d penciled in an acceleration to 0.9% from the prior quarter’s 0.7% pace. Instead, the 1.3% print marked the fastest pace in the series’ 39-year history. The hits kept coming yesterday, with the spike in third quarter Unit Labor Costs to 8.3%. Once again, economists anticipated a massive pop of 7.4% from the second quarter’s 1.1% rate. If you net out the violent moves induced by the pandemic, labor costs grew at the fastest pace since 2014’s first quarter. The mirror image – productivity – collapsed at a 5% rate, its worst showing since 1981. We know there are massive disruptions that continue to plague the bean counters’ best efforts; there is no doubt an element of distortion that suggests you fade the magnitude of these moves. But we are talking quarterly series in all three cases, which cannot and will not be ignored inside the microcosm of PhDs at the Federal Reserve.

Whatever will Jay Powell do if wage inflation persists for several more quarters? We hate to use the term “conundrum,” but that’s what he’s facing. In Wednesday’s painful post-FOMC presser, in defiance of Merriam-Webster, he bumbled about trying to convince himself that “transitory” was measured subjectively. Powell is desperate to buy time with such nonsense. And we would argue that he a leg to stand on as it pertains to the most pernicious form of rising costs – wage inflation.

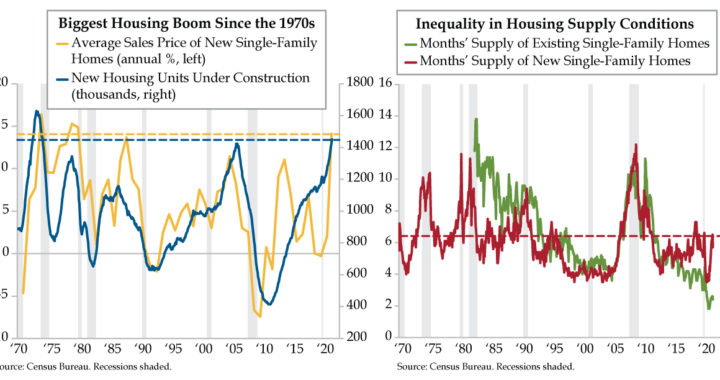

Achieving “maximum inclusive employment” by June 30th would be a miracle and Powell knows it. That’s why he’s deluding himself that he won’t have to quicken the pace of the taper much less hike rates come July. Viewers of the press conference may have noted the most confrontational interaction with reporters we’ve seen since Pedro da Costa asked Janet Yellen about the Medley scandal. The highest inflation many have experienced in their lifetimes is undeniably a regressive tax, harming lower-income earners appreciably more than their high-income-earner counterparts.

That’s what brings us to the above referenced leg Powell has to stand on and defines the dilemma he faces as tightening into a slowing economy never ends well. This point may not resonate with those on the receiving end of soaring wages. But it sure does with the lowest income earners who’ve slashed their budgets to accommodate the higher costs of essentials, from housing to groceries to gasoline. And that’s the case for those with incomes. As you see in today’s left graph inset, the labor force participation rate (LFPR) among Whites (yellow bars) has recovered to 65.7% from February’s 68.0%. We’ve seen appreciably less of a bounce back in the LFPR of Blacks (red bars), which has moved down from 63.1% to 61.3%; Hispanics (blue bars) have fared about the same, with their rate at 61.5% vs. that which preceded the pandemic of 63.2%.

The blue-shaded area of today’s right chart fills in another blank. If you tally the number of Black and Hispanics who are unable to or not looking for work due to COVID-19, you see an enormous improvement from May 2020’s peak of 22.7 million. But the 2.8 million who remain is still a materially high figure. Think about how skyrocketing childcare costs factor in disproportionately for those who earn the least. Moreover, these same workers are also the least likely to have jobs that can be performed remotely.

We present the data on LFPR and those who’ve been yanked out of the workforce to contextualize the unemployment rates, which can’t properly reflect these elements. Even so, the unemployment rate recoveries are still nowhere near the “inclusivity” Powell aims to achieve. Since February 2020, the unemployment rate for Whites is 1.1% higher (blue line) while those of Blacks (red line) and Hispanics (blue line) remain 2.0% and 1.9% higher, respectively. As for permanent job losses, in the case of White workers (green line) they number 160,000 more than they did in February 2020 vis-à-vis Blacks (orange line) at 174,500 and Hispanics (purple line) at 214,500. Even against the backdrop of clear labor market scarring, the fireworks promise to continue in coming months.