VIPs

- Single-family home builder confidence inched up in September, per the National Association of Home Builders, on lower lumber prices and strong housing demand; despite the optimism, the housing sector continues to face supply chain issues and labor challenges

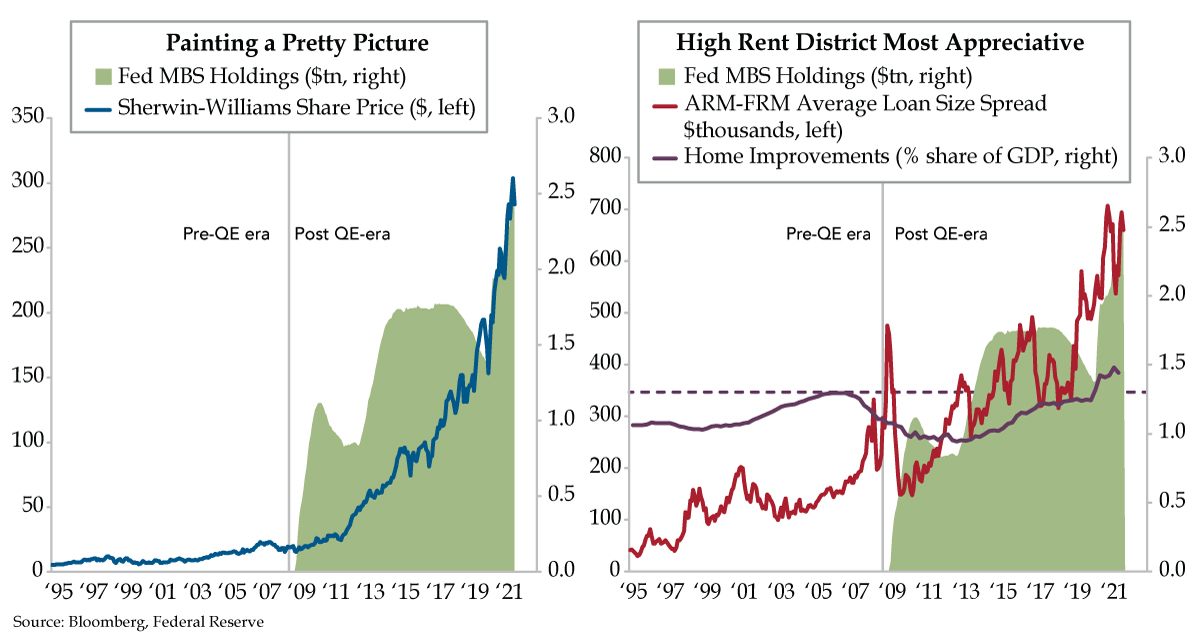

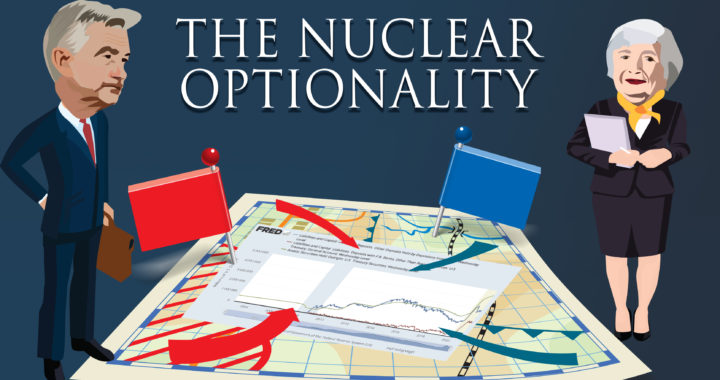

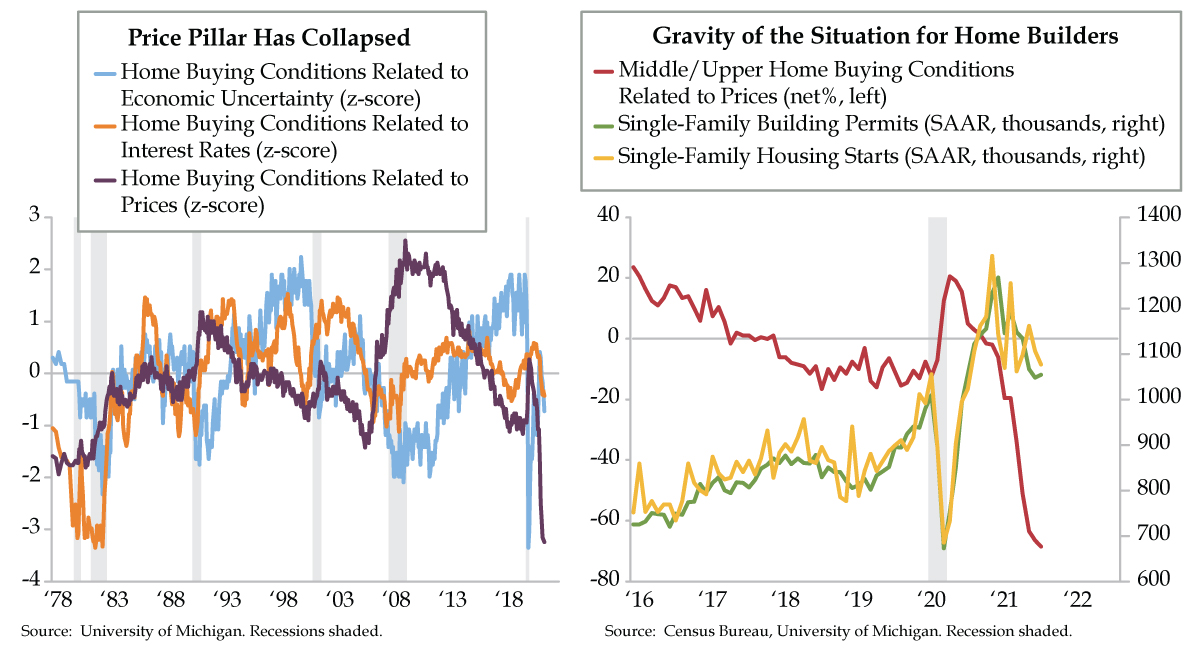

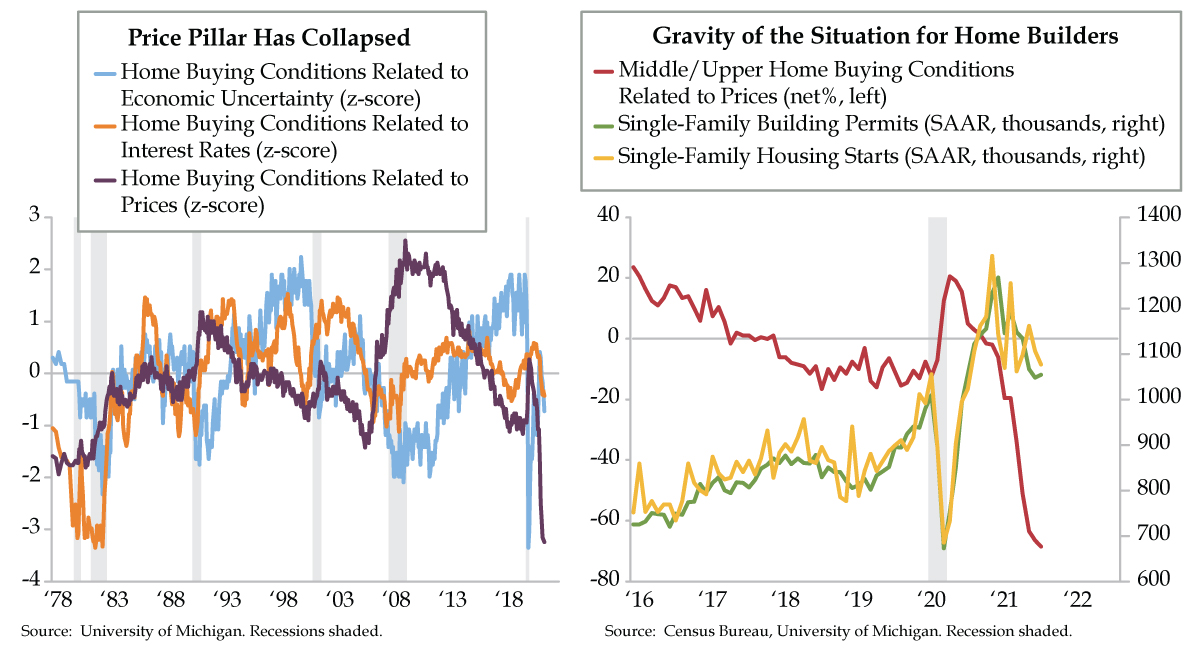

- Buying conditions posted a -3.24 z-score in September, well south of corresponding readings for interest rates, at -0.44, and economic uncertainty, at -0.73; despite sky-high selling conditions, the housing cycle appears to be rolling over, in light of stiff headwinds to demand

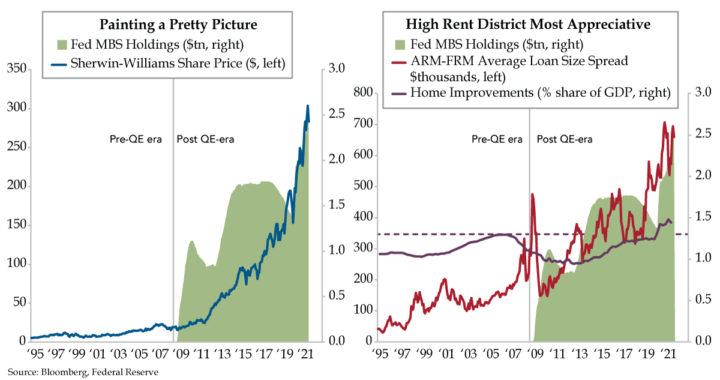

- Purchase volumes tracked by the Mortgage Bankers Association and Optimal Blue are now back in sync for the first time since the pandemic began; with both series seeing double-digit YoY drops, the Bloomberg consensus that housing starts stay flat appears overly optimistic

Merriam-Webster defines conventional wisdom as the “generally accepted belief, opinion, judgment or prediction about a particular matter.” For instance, conventional wisdom in Hollywood says that a movie can’t succeed unless it stars a famous actor or actress. The term dates back to 1838, but more often than not, it’s credited to the economist John Kenneth Galbraith, who used it in his 1958 book The Affluent Society. Galbraith wrote: “It will be convenient to have a name for the ideas which are esteemed at any time for their acceptability, and it should be a term that emphasizes this predictability. I shall refer to these ideas henceforth as the conventional wisdom.” The two-word phrase was used throughout the text to explain the high degree of resistance in academic economics to new ideas (imagine that!).

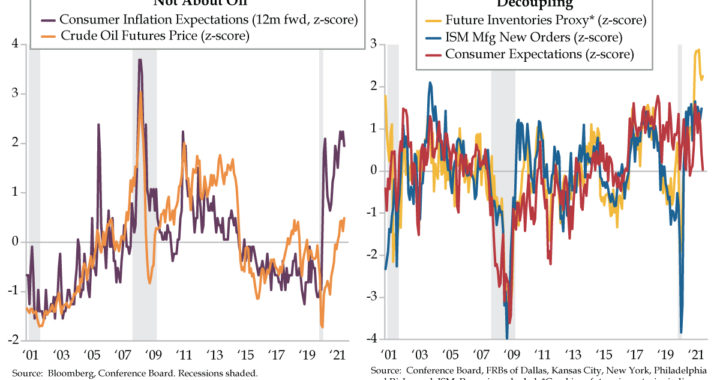

In the current economic environment, the narrative of a tight supply chain and labor market generate the mantra that supply limits demand. It’s understood that varying capacity constraints create a natural headwind to expansion. Call this the conventional wisdom of the day.

Let’s apply this to the housing sector. On Monday, the National Association of Home Builders explained that single-family home builder confidence inched up in September on lower lumber prices and strong housing demand, even as the housing sector continues to grapple with building material supply chain issues and labor challenges. Lumber prices, construction material costs and construction worker wages are easily illustrated – and have been closely watched concerns on the cost front. Strong housing demand, so the rote thinking went, was assumed.

Before digging deeper, buying a home is the largest financial commitment the average U.S. household makes. Acquiring the keys and crossing the threshold means buyers finance home purchases with residential mortgages. There are three pillars to such financed purchases: 1) prices, 2) interest rates and 3) unemployment.

Price determines the capacity to commit — there’s an inherent affordability quotient involved in a high versus low price backdrop. The former whittles buyers out of the equation; the latter fills the potential buyer pool. Because a large majority of homes have a six-digit price tag and most buyers finance, interest rates allow the interested parties to pay over a longer period of time to meet the monthly budget.

Ergo, in the ultimate analysis, unemployment dictates when the housing cycle begins and ends. To articulate the obvious, a falling trend in joblessness breeds lender optimism, while a rising path creates pessimism. Unemployment is akin to creditworthiness, and bankers slide up and down the tightening/easing scale depending on where the economic cycle is residing.

Where are we now? The price pillar has collapsed. The white hot buying conditions advanced lightning fast from reticence to successively higher highs in in 2021. The September level (purple line) printed at a -3.24 z-score (deviation from the mean adjusted for volatility), well south of that of the corresponding readings for interest rates (-0.44, orange line) and economic uncertainty (-0.73, light blue line), the proxy for unemployment.

The biggest refutation to the narrative is home selling conditions, an alternative guide to housing demand. We can’t deny that home selling conditions related to prices hit an all-time high in August. Home sellers prefer to sell in a rising market – and this market supremely qualified. But the pool of home sellers is smaller than the pool of home buyers. Homeownership rates in the U.S. are not 100%, they are closer to 65%. So, home selling conditions can never provide the whole picture.

Most owned dwellings in America are purchased by middle-income and upper-income households. We approximate about 85% of home sales are made by these two cohorts (using Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey data). Since this represents the lion’s share of purchases, understanding how these buyers feel about prices in the current environment is instructive for judging niggling challenge to demand. In sum, they’ve never been more pessimistic.

The right chart depicts an aggregate indicator of middle-/upper-income home buying conditions related to prices. The plunge is historic. The gravity of the situation also suggests demand is facing stiff headwinds. If anything, the gut reaction by these buyers is postpone the purchase until prices move to your favor. Anyone have an answer when that will be?

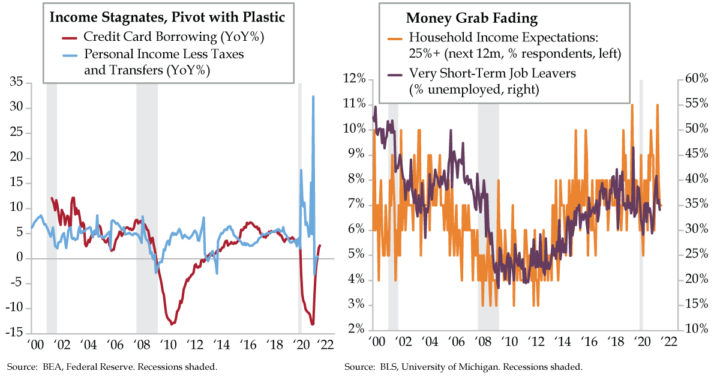

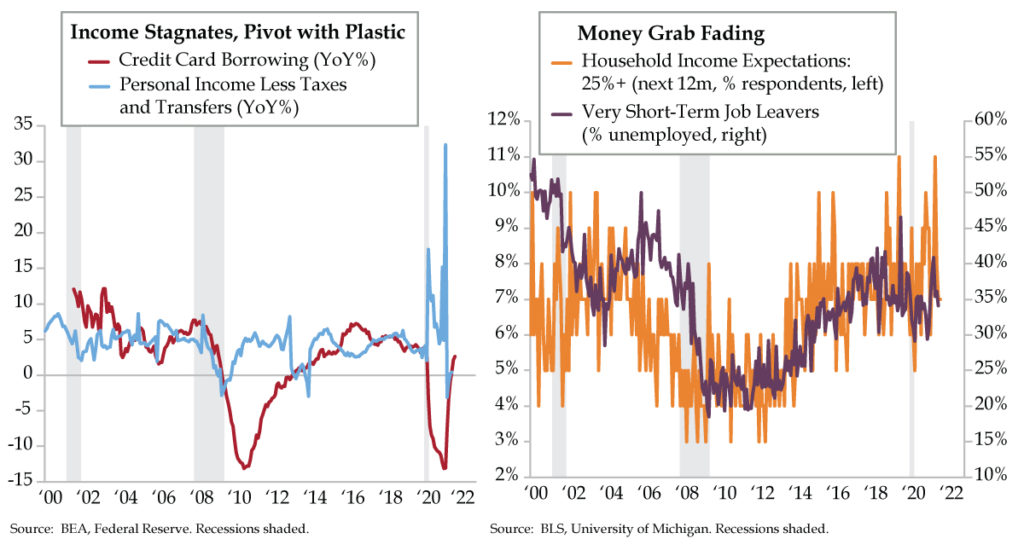

One corroborating signal for demand is coming from mortgage application activity. Home purchase volume tracked by the Mortgage Bankers Association and from Optimal Blue are back in sync over the last six months for the first time since before COVID hit. According to the American Enterprise Institute Housing Center, both series are “the best indication of lending reality going forward”, and both are posting double-digit year-over-year declines.

Conventional wisdom from Bloomberg’s consensus estimates for housing starts project a relatively flat profile over the next four quarters. This would imply a steady revenue path over the next year for home builders. In our view, this seems somewhat overly optimistic given the unprecedented developments regarding home buying conditions that have unfolded for the biggest buyers of homes in America.

As if we needed more corroboration, QI amiga Phillipa Dunne parsed Zillow data concluding that sales were slowing, inventory was rising and more price concessions were prevalent, adding that “returning to earth from the stratosphere is likely to be a shock in some type of way, as the Zoomer kids say. From this Zillow data, it looks like reentry has begun.” We humbly concur.