VIPs

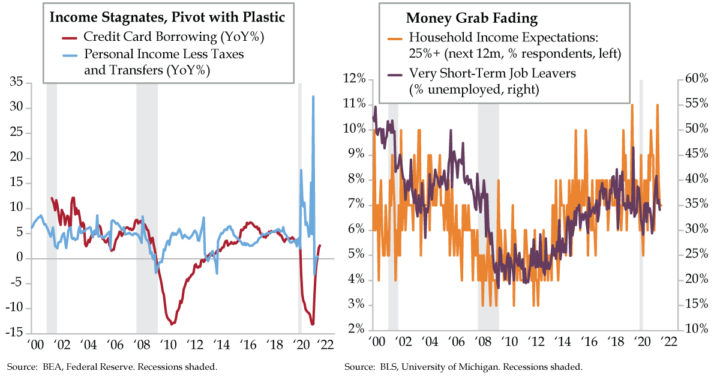

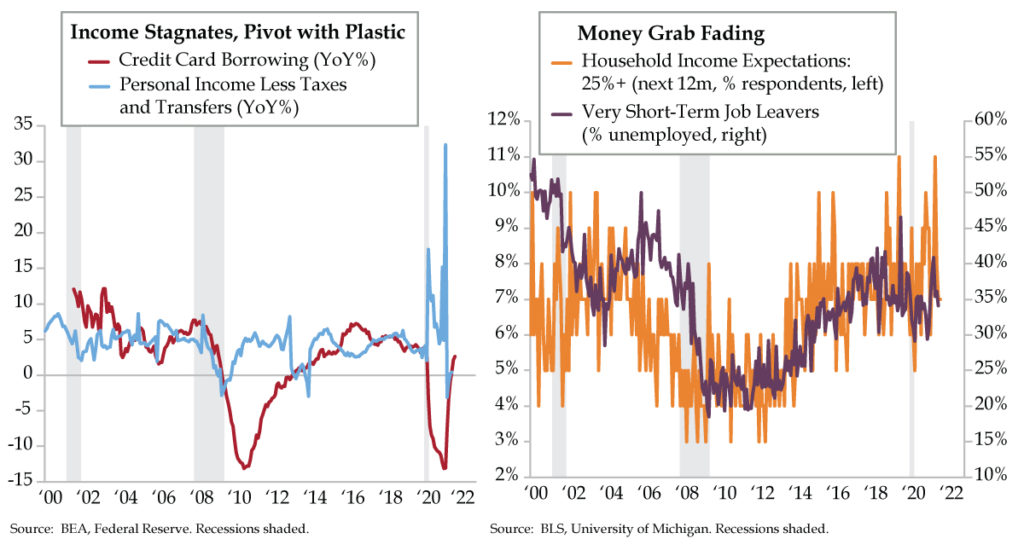

- The YoY trend in personal income, less taxes and transfers, has seen its forward momentum stall in recent months, per BEA data; at the same time, credit card borrowing has ramped up significantly, posting the first gains on a YoY basis since the pandemic began last March

- At 1.6%, 12-month Household Income Expectations, per the University of Michigan’s Consumer Survey, have not yet returned to pre-COVID levels north of 2%; with current CPI at 5.3% YoY and short-run expectations at 4.7%, the hit to purchasing power is notable

- After hitting a record high 11% in June, those expecting incomes to rise by more than 25% fell to 7% in September, in line with the long-run average; a decrease in short-term job leavers, from 40.9% of the unemployed in May to 34.1% in August, confirms the trend

The joy of parenting doesn’t come with a handbook. But certain rules of thumb that may get passed down by the generations can become good advice to follow. For example, take the idea of choice. For the rug rats in your life, psychologists recommend giving your children only two choices at a time when they want to make decisions. Kids want and expect their parents to provide structure and make key family decisions. It helps them feel safe. While it’s great to give kids a say in things, too many choices can overwhelm them or put too much pressure on them.

When reacting to inflation, it feels like the Fed has conditioned financial markets to think in two ways. It has done this by taking one side of the argument – the Fed believes inflation will be transitory. Therefore, the other side of the argument is the opposing view, inflation will be persistent.

Last Friday’s University of Michigan (UMich) consumer survey dug into households’ potential reactions to inflation. The first one was in the context of a transitory rise. In this case, consumers were seen postponing purchases and slowing spending in the months ahead. Once the temporary period of higher prices ended, consumers would resume spending at a quicker pace and a rebound would ensue.

The second reaction put inflation persistence under the umbrella of a significant fiscal and monetary expansion. Inflation psychology would develop, and greater demands for wage increases would be part of the outcome. To judge this version, however, would take time because long-term inflation expectations would have to become unhinged, not the case in the UMich survey.

UMich survey director Richard Curtin didn’t stop the discussion there. He illustrated a third option (bolding ours):

- “The final alternative is that consumers may believe that the most effective strategy to maintaining their purchasing power is to emphasize increases in their incomes, net of taxes and transfers. The effectiveness of pandemic transfers were shown to be successful in offsetting hardships among those most vulnerable to economic disparities. Transfers to offset the inflationary erosion of living standards would be justified in a similar manner.”

The third reaction has an agnostic quality regarding the transitory vs. persistent dispute by focusing on purchasing power instead. This puts the onus on consumers to find a way to more than offset the headwind from higher prices. That can be done by increasing income, cutting household budget costs or a combination of the two.

Before exploring that, we illustrated personal income excluding taxes and transfers. What we discovered was that the year-over-year (YoY) trend has stalled in recent months (blue line). Forward momentum has essentially stopped. In its place, credit card usage has ramped up significantly (red line), posting the first post-COVID gains on an annual basis since the pandemic first hit.

Optimists would opine that the recovery in income expectations has made households more comfortable using plastic to borrow tomorrow’s income today. Pragmatists would respond that there has been progress on the income expectations front, but not substantial.

Median income expectations from the UMich survey have not returned to pre-COVID levels north of 2% despite recovering from last year’s involuntary shutdown abyss by the fall of 2020. The current 1.6% tally implies a stagnation of sorts. Since April 2021, household income expectations over the next twelve months have traveled in a tight range (1.6% to 1.9%). The hit to purchasing power is decidedly large when you factor in current inflation (consumer price index at 5.3%) or even short-run household inflation expectations (UMich one-year figure at 4.7%).

The UMich survey also illustrates how consumers can emphasize increases in their incomes. Twelve-month forward income expectations are broken down into a number of buckets: 1-2%, 3-4%, 5%, 6-9% 10-24% and 25% or more. To best offset the squeeze from prices, more consumers would look for ways to generate the biggest boost to their future income. That happens when the 25%-plus bucket swells significantly. That’s usually when more consumers opt to jump ship for better paying opportunities, much better paying. Job leavers or voluntary quits surge.

Unfortunately, this dynamic peaked in the spring and has faded through the summer months (orange line). Consumers expecting to earn 25% or more in the next year matched a record high 11% in June. By September, this guide fell to 7%, in line with the long-run average. The move away from the right tail can be confirmed by a fall back in “good unemployment.” This oxymoron defined as very short-term job leavers surged from 29.4% of the unemployed in January to 40.9% in May (purple line). It has since fallen back to 34.1% in August.

The third option of bolstering purchasing power no longer has the wind at its back from a money grab perspective. It would take another surge in workers deciding to test the waters for better pay in order to help offset the most bearish price developments in decades for buying conditions for autos, homes and home goods. Without true gains in purchasing power through the income channel, stagflation risk would continue to fester. This is a key test of the sustainability of the rebound in consumer spending.