VIPs

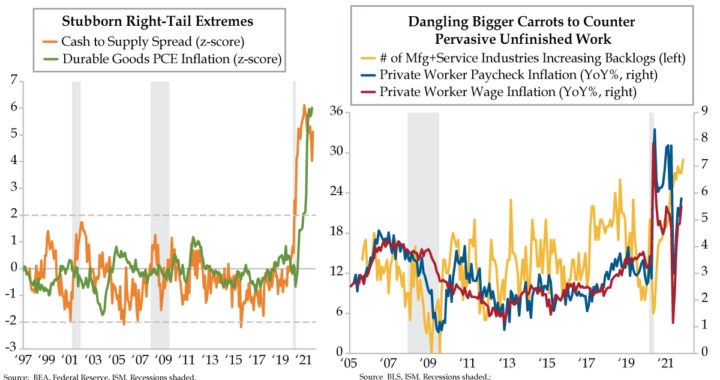

- The Cash to Supply spread, comparing cash equivalents to ISM inventories, has been above a +2 z-score for 18 months and was +5 in October; the series leads durable goods inflation, which snapped its 25-year deflationary trend last year and registered a +6 z-score this month

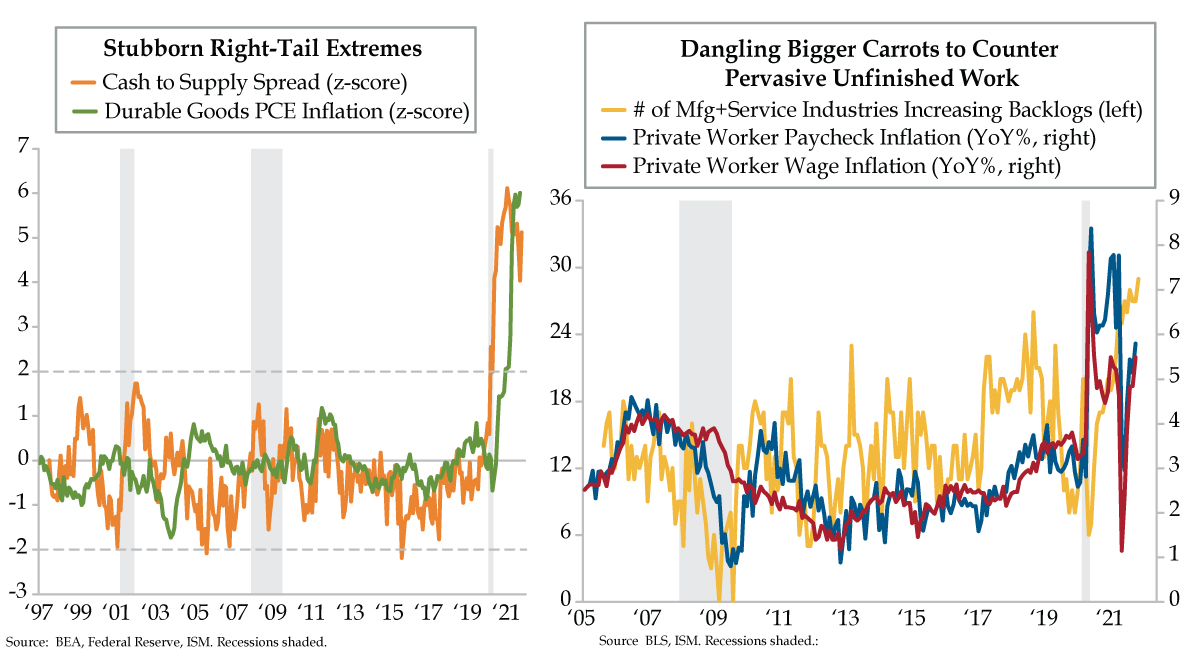

- Per ISM, backlogs are increasing in 29 out of 36 industries across manufacturing and services, a record high; as a result of the bottlenecks, the U.S. labor market is seeing earnings growth in the right-tail, with both paycheck and wage inflation above the 5% YoY threshold

- Yield curves steepened after yesterday’s tapering announcement by the Fed, though Powell held firm on decoupling tapering from rate hikes; however, the potential for further flattening long-term remains strong as evidence continues to defy the transitory narrative

“Excuse me, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the action on this piano.” And at that point, the proprietor of Ray’s Music Exchange sat down at the keys and broke into an upbeat rendition of “Shake a Tail Feather” prompting the whole neighborhood to show off their best dance moves. It was all done to convince The Blues Brothers that the electric piano — for which Ray (as in Charles), was willing to throw in the black keys for free — was the best in Chicago. There never was an actual store called Ray’s Music Exchange. The mural everyone danced in front of on the Prairie Avenue side of the building at 300 East 47th Street in Chicago was painted during the production of the cult musical comedy in 1979. Among the artists depicted were Charles himself, Muddy Waters, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, Dizzy Gillespie, Curtis Mayfield and Stevie Wonder. Sadly, the wall painting that celebrated these great musicians and drew fans of the movie from around the world for 40 years was sacrificed when the building was demolished following a fire in 2020.

Speaking of shaking tail feathers or just tail of a distribution… Regular readers appreciate our affinity for the great normalizer, the z-score. If you’ll indulge a bit of nerdiness, this metric contextualizes statistics in a standard normal distribution. There is a special normal distribution with a mean of zero and standard deviation of 1. The standard normal distribution is centered at zero and the degree to which a given measurement deviates from the mean is given by the standard deviation. For the standard normal distribution, 68% of the observations lie within 1 standard deviation of the mean, 95% lie within two standard deviation of the mean, and 99.9% lie within 3 standard deviations of the mean.

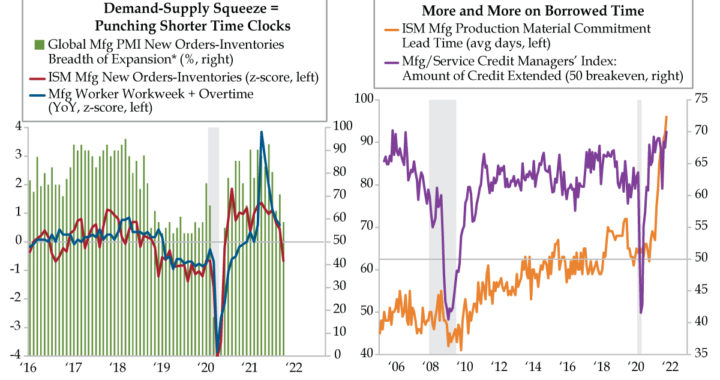

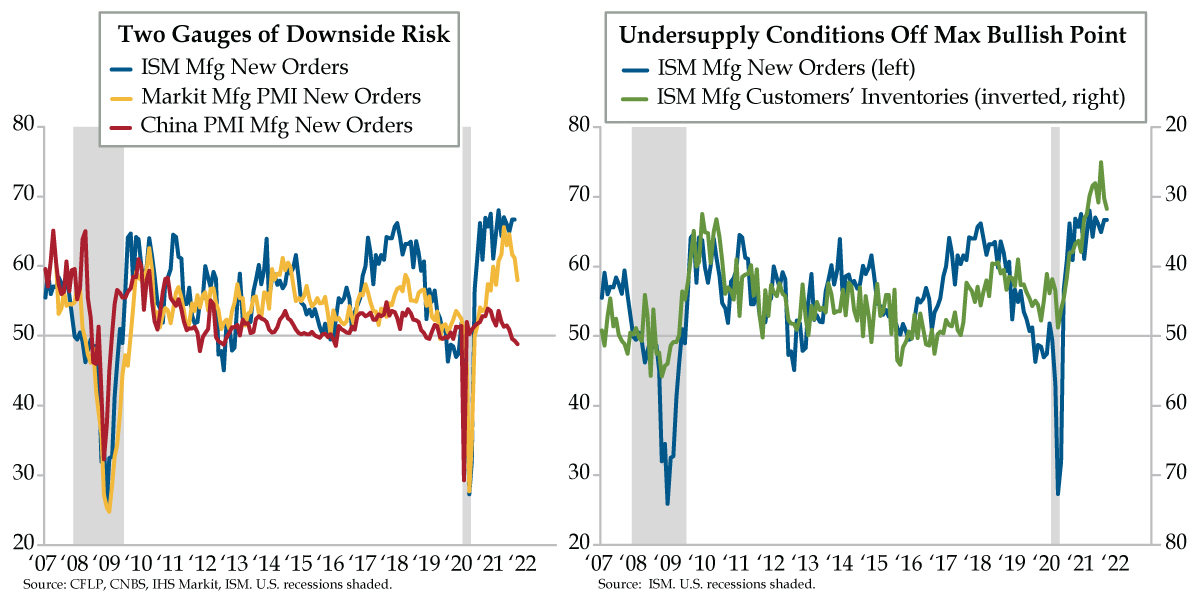

With that lesson on probability behind us, focus your lens on today’s left chart, which updates a chart we published in May. The Cash to Supply spread (orange line) is an inflation leader that combines cash equivalents (money of zero maturity, MZM) against inventory sentiment measures from both Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing and service reports. This gauge was created in the spirit of Milton Friedman’s “too much money chasing too few goods” mantra that all students of the dry science learn via osmosis with other economists.

The ebb and flow in the Cash to Supply spread has tended to track and lead that of pricing for durable goods over time. This is the part of the inflation mosaic that’s been significantly altered in the post-COVID era. For 25 years prior to the pandemic, durable goods prices were in deflation. That ended in 2020 and the segment’s inflation has stretched into 2021. The durables deflation/inflation rate has been z-scored (see above and simply put, deviation from the mean adjusted for volatility applied) to level the comparison with the Cash to Supply spread, which itself, is a difference of two z-scores.

Recall the standard normal distribution definition and examine all the data points that fall between the dashed horizontal lines of -2 and +2 z-scores. Most of them fall within that range. Only the far right of the chart has risen well north of +2 and has yet to show decided momentum to fall back within the usual historical range. In fact, the Cash to Supply spread has been obstinately above a +2 z-score for 18 straight months and most recently snapped back above a +5 reading in October, persistently flagging too much money chasing too few goods. Durable goods inflation has persistently exceeded +2 on the z-scale for 10 months in a row and in October registered a +6. This is not an episode of The Twilight Zone. These stubborn extremes continue to shake a tail feather at Team Transitory.

A large cash pile and an undersupplied supply chain aren’t the only right-tail observations that prevail today. As you see in today’s right chart, backlogs across the U.S. economy have become so pervasive as to be occurring in 29 out of the 36 industries designated by the manufacturing and service sectors combined (yellow line). This. Has. Never. Happened. Before.

Note that widespread backlogs signal unfinished work. To pare down the pile of domiciled inboxes from input shortages, transport delays and lack of warm bodies to fill positions, larger carrots have been dangled across the workforce in the form of higher wages. Longer hours go hand in hand with an environment of rising unfilled orders. Ergo, paychecks follow by fattening like Thanksgiving turkeys readying for slaughter. COVID base effects have washed out of year-over-year comparisons for wages (red line) and paychecks (light blue line). Readings above the 5% threshold for both gauges tell us we’re in a right-tail environment in the U.S. labor market.

It doesn’t take a legendary, blind soul music genius like Ray Charles to see that a leader of inflation in durable goods has persevered outside the distribution for the first time since the late 1990s and is refusing to normalize. Wage pressures also are bubbling as backlogs have never bulged to this extent. Yield curves steepened after yesterday’s Fed taper announcement as Fed Chair Powell held firm on divorcing the process of tapering from rate hikes. That said, those betting on a flattening bias should not be deterred. Team Transitory keeps losing its fan base.